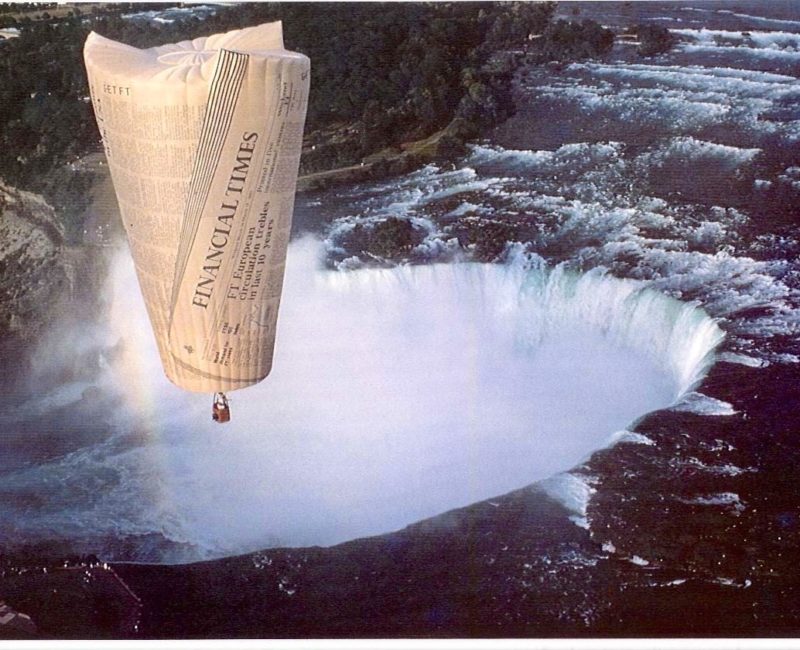

The FT balloon flying over the Niagara Falls

Daredevil adventurer and expedition leader, Peter Mason, organised the first hot-air balloon flight over Mt Everest. For the past 40 years, Peter has navigated the globe in search of fresh thrills and sometimes spills.

PH Peter, welcome to our travel podcast. Now, you followed a highly successful career as a newspaper reporter and foreign correspondent, with a second life as a commercial balloon pilot. However did this come about?

PM Well, it’s a long story, but I think we’ve got a bit of time to talk about it. I’d been working as a journalist for all my life from the age of 17, and it was now 1987 and I was news editor of The London Daily News which was Robert Maxwell’s new start-up, seven-day-a-week London newspaper, a 24-hour a day paper, which everyone said then wouldn’t work in the UK – and they weren’t wrong because it lasted five months and folded. At which point I found myself unemployed, and at the age of 44 virtually unemployable because I couldn’t go back to my old job with my tail between my legs. I couldn’t think of anything else I might do in Fleet Street that would further my career, and I thought, maybe it’s time for change.

So I hit on this idea of starting up a hot-air balloon company, as one does. I went home. I said to my wife: ‘Sheila, I’ve got this wonderful idea how we can restart and make a living for ourselves after being made redundant – I’ll start a hot-air balloon company.’ And she looked aghast and said: ‘In that case, I’ll go get a job,’ which she did. And I started the balloon company. And after three months, when she realised that I was serious about what I was doing, and that we could make a living out of it, she joined me as my partner and we set up The Aerial Display Company which ran for over 20 years.

PH Did you have any experience of hot-air ballooning at this stage?

PM I had been involved in quite a few hot-air balloon projects, and in fact I used to write a column for The Daily Express in my spare time. Not that I had much of it, but what spare time I had, I used to go out and indulge myself to the full in adventure sports – things like hang-gliding, skydiving, ballooning, flying microlight aircraft, rock climbing, scuba diving, anything that had a bit of an adrenaline rush to it. And downhill skiing, of course – I wasn’t very good at it, but it was quick. And I got involved in all these adventure activities and I didn’t just go out there and do the things – I didn’t just go and ski or skydive or hang-glide or dive the ocean depths – I would actually go there and get a license that qualified me to do it properly. And I actually learned the skills, and ballooning was one of those skills.

Peter helping the then Crown Prince of Bahrain, Shiekh Mohammed, in the captain’s seat of a Cloudhopper balloon in Meribel

PH So how do you actually go about becoming a balloon pilot? You were sitting at your desk at The Daily News and you decided, I’m going to be a balloon pilot? What’s the next step?

PM It wasn’t quite that simple. But I mean, first of all, if I was to make a living out of ballooning, I had to find a client, a client who felt that a hot-air balloon was a good medium for promoting the company and a good way of entertaining guests and for projecting one’s name at a higher level and on a different plane. So I had to find a client and I hit upon this idea – I learned that it was the Financial Times’ 100th anniversary coming up the following year, 1988. And I thought: now that could be a great wheeze to design and build a balloon in the shape of a rolled-up newspaper.

I went to the Financial Times with this proposal and I said: ‘I know you’ll think I’m mad but if you put your name on this balloon, I’ll fly it all over the world. I’ll project your image and promote your name and I’ll elevate your position in the newspaper marketplace.’ And they said: ‘That’s a good idea. Let’s have a go at it.’ So I signed a contract and they gave me some money. I designed and built a balloon for them and the rest is history.

PH But I understand there was just one rather major problem?

PM The fact that I hadn’t actually formed a company at that time and didn’t have a balloon pilot’s license? I wouldn’t say I bluffed my way round the problem, I worked around it in a sensible way. I said, look, I do have quite a lot of ground work to do before I could put this thing into action. But they were patient, they weren’t in a hurry. They also knew that I was hungry, so I would work very hard to make sure it succeeded. First thing I did: once the FT said: ‘Yes, we’d like the idea, can we go with it?’ I got on the phone to Robin Batchelor, who was an old friend of mine. He was a very well-known UK balloon pilot, and still flies to this day. And he had recently taught Richard Branson to fly a balloon, so he had a good pedigree. I signed Robin up and for the next six weeks worked very hard, morning and evening, learning the skills of flying a balloon. It is not just getting in the basket, turning on the burner and off you go. You’ve got to actually study the same curriculum that commercial airline pilots use, for example, because we’re all flying in the same airspace. So if you’re flying a balloon commercially around airports and around cities, you have to have the same kind of knowledge that the pilot has. So it’s quite hard work in terms of learning navigation, meteorology, systems, how everything works. And being in charge of a balloon is like being in charge of an airplane – it is an aircraft and you have to be licensed to fly it. So it took me a few months to get my private license and from there I went on to get my commercial. Hard work, but worth every penny.

The Michelin balloon at Sydney Harbour

FH How do you actually steer a balloon?

PM You don’t. The wind steers for you. You go with the direction of the wind. Balloons have no motive power of their own. They have no engine, no rudder, no ailerons, no flaps, no controls like an airplane. It’s a big bag of hot air, basically, and you always inflate the balloon upwind of where you want to fly and land. So if you were to take off from, say, your house in Winchester and fly to Basingstoke, because the wind varies in direction at different heights, you can steer the balloon left and right by climbing and descending. And that’s how you pinpoint your landing point, you come into land, and if you’re good and lucky – and it helps to be both – you land.

FH How do you know which way to go? Does the balloon have a sat nav? Or do you just do it visually?

PM Well, these days, yes, most parts of the would carry a sat nav device. In those days when I started flying in in the early 1980s – I had been flying balloons before I actually went out to get my license, but I hadn’t been a licensed pilot, but I had done quite a bit of flying with other pilots and I did know how to navigate and how to read a map.

It’s much easier these days to have a sat nav because tells you exactly where you are, what town you’re flying over. In those days, all you had was latitude and longitude. You always fly visual with the balloon. You don’t fly at night; you don’t fly in cloud. So you’ve got a map and you take off, and you’re only flying at five or 10 knots, which is to six or twelve miles an hour. You take off and you use your map to guide you. So, you know you’re flying over this village or that village and you know exactly where you are at all times.

PH Well, the thing that’s always puzzled me is how do you land and how do you decide where to land? And you can land anywhere?

PM Pretty much. You have to take take cognisance of the lay of the land. You have to make sure you don’t fly low over horses or livestock and frighten them, that you don’t anger farmers. For example, some farmers don’t like balloons landing on their property. Most of them are in fact quite agreeable to it. These days, most commercial bird operators have agreement with the local farmers that they pay them a fee, whenever they land or take off. But normally you land where there’s a clear bit of ground, a rugby field is good, a school playground providing their aren’t children playing in it. Even a road, if it’s empty, and you choose your landing spot when you take off, as you take off, you look ahead. We work on calculating wind speed and direction, the time to destination, and you say ‘I could reach that point in 25 minutes.’ I will aim to land there and by climbing and descending, you see the balloon into the landing area.

Peter, left, in the FT balloon

PH So while you’re learning how to become a balloon pilot, presumably someone is building this magnificent balloon for you?

PM Yes, indeed they were.

FH How do you build a balloon?

PM Well you go to a manufacturer like Don Cameron. Cameron Balloons in Bristol or Per Lindstrand in Oswestry, manufactures in other countries. Spain: Ultra Magic, the USA: Balloon Works. You take your idea to a balloon manufacturer and you say, ‘This is what we want to do. Can you turn this artwork or this drawing or this concept into a machine that will fly?’ And some of them are very difficult. I mean, we had the Financial Times, for example: 110 feet tall, three peaks, like a rolled up copy of a newspaper, like like an ice cream cone in shape. And every single letter, every single word on the side of the balloon was painted on by hand. And there were 100,000 characters all together, all of which I wrote – I put the whole thing together like I was editing the newspaper, like I was preparing a newspaper publication. It became a flying copy of the newspaper.

PH Then having got the balloon, you had your maiden FT flight. Where was that?

PM Over Tower Bridge in London. And sadly, I wasn’t there for the flight. I had to bring in Crispin Williams, who was one of my instructors who worked for the balloon manufacturing company. I brought him in to fly it for us over Tower Bridge, Sheila and I were on our way back in the United States, where we had just achieved a new world record with Per Lindstrand who manufactured out of Oswestry.

We’d reached a height of 65,000ft in a hot-air balloon – world record never been broken to this day. This was in 1998, so we’re talking about 30 years ago. And we weren’t able to be at the launch of the FT, but we then took the FT on a European tour followed by a world tour. We flew the balloon altogether in 38 countries and over every almost every capital city in the world, certainly in Europe, North America, Australasia and parts of Asia and South America, I mustn’t forget Rio de Janeiro.

PH So having done this fairly remarkable feat, you then looked to a higher mountain to climb?

Star balloon taking off from Kathmandu

PM A company approached me and asked me if I would be prepared to put together a team and a project to fly a hot-air balloon over the summit of Mt Everest. I was a bit taken aback at first, I thought, it’s never been done before. There have been attempts that have been unsuccessful. It’s fraught with danger flying over the Himalayas, the highest mountain range in the world, flying over the highest peak in the world: 29,000ft. At the time we were planning to do the Everest flight, there were no hot-air balloons that were designed to fly any distance at all at that kind of altitude. We’re talking about flying over a mountain that’s nearly 30,000ft high, so you’re looking at a balloon that can fly at 35,000 to 40,000ft to give clearance to the mountain. So we required that a special balloon had to be built and a special burner also had to be built, designed specifically for the job.

We put together a team of 14 crew, which included cameramen, sound men, technicians, engineers. On top of that we had 20 sherpas, 50 porters, 90 yaks, a helicopter and a high-altitude plane. We had two cameramen, one in each of the balloons, plus a film crew on the ground who were making a film for National Geographic and also Channel 4 television. I was project director and expedition leader. The whole project took three years to assemble, and to succeed in flying over Everest we had two unsuccessful attempts, one of them interrupted by a coup d’etat in Nepal, followed by the third, which succeeded, in 1991. And it was quite an achievement. I mean, no-one’s ever done that flight since and nobody needs to because you can’t break a world record for the first time, twice. I mean, who remembers the second man to fly the Atlantic solo after Lindbergh?

FH How did it feel achieving something like that? It must have been amazing.

PM It was good, a good warm feeling. It took a lot out of us. It took a lot out of the company as well, because at that time we’d gone from being quite a small ‘mom and pop’ company with just two or three small clients. We had already acquired three or four other clients at that time. Hawker Siddeley, Lucas Aerospace, Star Micronics who had financed the Everest expedition, Motorola, Longman Chronicle the educational publisher, and during the course of putting this project together took us three years and took a lot out of us. And it also meant that we couldn’t concentrate as much as we would have liked on building the core business, which was flying special-shaped balloons to promote clients as an advertising publicity medium.

So we did take a bit of a knock on that; it took us a few years to recover and get our feet. Then along came Michelin, kept the business going for a good few years after we had considered selling the business and retiring. But we got a magnificent contract with Michelin, the French tyre manufacturer, the international company. They wanted to commemorate the 100th birthday of Bibendum the Michelin Man. And we came up with the idea of a hot-air balloon in the shape of the Michelin Man and we thought that they’d be quite happy to have one of those. In actual fact, they ordered four, and seven regular-shaped balloons. So we ended up with the world’s biggest: 11 balloons in one contract, which we operated around the world for nearly five years.

Once you’ve got the hardware, once you’ve built, you’ve invested the capital to build the balloons and you’d made a reputation because of flying them all over the world, you want to keep doing it, and Michelin couldn’t let go. So they actually carried on with the contract for another five years after the initial years. It was a lot of fun. We had four Michelin Man special-shaped balloons 175ft tall, enormous, among the biggest balloons ever built. Difficult to fly, heavy to work with, hard to pack away, they required a pilot and four crew minimum – sometimes six – and big vehicles and a big trailer. A lot of hard work, a lot of planning. We had these balloons flying all over the world. One time we had 11 of 11 Michelin balloons in the air any one time all over the world, that’s quite a quite a handful.

Bibendum the Michelin Man

FH And you once flew over the Niagara Falls. Was that with Michelin as well?

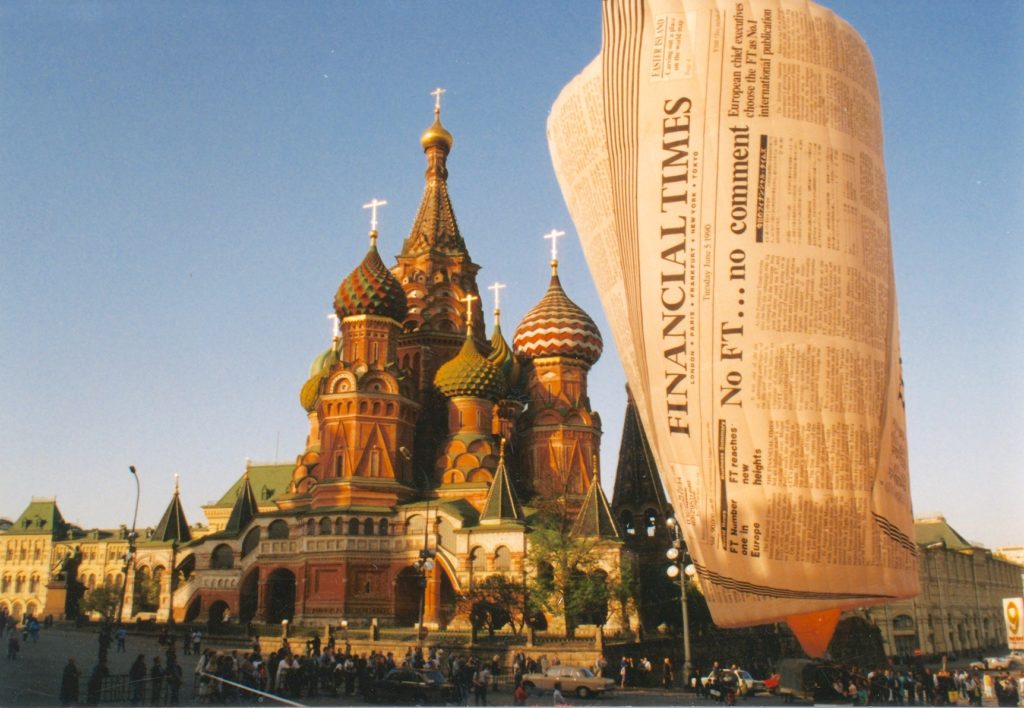

PM Those was for the Financial Times, that was back in 1992. We were shooting a calendar for the 100th anniversary of the FT turning pink. Initially the FT was white like every other newspaper, and in 1893 it changed colour and became pink because they thought it would stand out more against its competitors. So we took the balloon around the world. We took it to Wadi Rum in Jordan for King Hussein’s birthday. We took it to China, we took it to Hong Kong, to Singapore, all over Europe, Eastern Europe as well – we flew Warsaw, Prague, we took it to Moscow. And every one of these venues was a photo shoot. And every photo shoot provided us with pictures for this amazing calendar that we produced, 5,000 copies limited edition, for the FT’s favourite clients. I still have a copy in my drawer and it’s a treasured possession. I mean, we flew the balloon in front of the World Trade Center in New York.

PH There must have been some difficult moments and indeed some dangerous moments?

PM There have been a few ‘interesting’ moments, I’d call them. I’ve not had any serious mishaps with a balloon, I’ve not had any accidents. I’ve had a couple of what you might call ‘heavy landings’. Any landing you walk away from is a good one because a balloon landing is, in actual fact, a controlled crash. And how well you control it depends on how happy your passengers are and how well the flight could be deemed to have gone. I mean, somebody asked me once, how do you land a balloon? You choose a bit of land to land in, and you try and put the balloon down there. It is quite hard sometimes. You sometimes come down quite quickly, come in fast and it can be a bit hairy. Balloon landing is a controlled accident and any landing you walk away from is a good one. And I’ve had lots and lots and lots of good landings, about 3,000 in total. I’ve had one or two interesting landings. Yeah, I mean, bad in the sense that, yes, I had an accident doing a balloon race in the Alps in 1998.

Every year there is a big alpine balloon festival in Chateau d’Oex in Switzerland, which is quite near to Gstaad, and it attracts some of the world’s top balloonists and their sponsors, up to 100 balloons at a time attend, and watching the launch in that mountainous terrain in that lovely Alpine region surrounded by snow-capped peaks is a sight to behold. We took the Financial Times balloon there I think eight times. We launched the Michelin Balloon Team in Chateau d’Oex in 1998. It was at that launch that I took part in one of the annual trans-Alpine balloon races called the David Niven Trophy. David Niven, named after the famous actor who lived in Chateau d’Oex for many years and who, in fact, is buried in the cemetery right next to the balloon launch field. So when you take off, you look down at the ground and see David Niven’s grave. Every year they have a Coup David Niven and it’s a long-distance balloon race: you take off at Chateau d’Oex and fly as far as you can, as far as the wind will take you. I think the record is something like 176 kilometres. And they ended up in in eastern Yugoslavia, as it was then.

I was taking part in that long-distance race in 1998 at the launch of Michelin Balloons, and we ran into some bad weather, we were given a forecast that indicated it would be clear of cloud, and that there was no wind – or light winds – in the Rhone valley. As it turned out, it was cloud cover. The whole of the Alpine region was socked in and we didn’t see the ground from when we flew over Lausanne until we hit the ground 176km later on the edge of the Rhone Valley where the Mistral was hurtling along at 100mph. When we came in to land, the wind was blowing quite hard. We were travelling at about 70 knots, which is about 75mph, 400ft-a-minute down. And we went through trees, I got knocked out of the basket. The balloon flew on for another half a mile on land and came to rest on the edge of the ravine with 1,000ft drop on the other side.

I ended up in hospital with a fractured wrist, crack sternum, four broken ribs, internal injuries, facial lacerations and a dislocated knee, which almost required amputation. And that’s the only time I’ve actually had a bad landing, a wonderful flight with a bad landing and it doesn’t happen very often. And I still maintain ballooning is the safest form of aerial travel. But that’s the only time I can think of that I had what I would call an accident – it wasn’t doing a passenger flight or flying clients, flying guests for a client. It was taking part in a trans-alpine balloon race, which is totally different – like the difference between driving to the supermarket and driving in a race car.

PH Peter, you specialise in narrow escapes. Indeed you’ve written a book called Narrow Escapes I believe?

PM The Book of Narrow Escapes. Yes, one of my pet projects back in the ’80s.

PH You had another narrow escape yourself, I believe. You jumped out of a plane and had a parachute problem?

PM Yes, I did. In fact, it was my 13th parachute jump funnily enough. And it was a place called Pope Valley in California and I’d gone over on behalf of the Daily Express with the British parachute team in training for the world championships. And one of the things, one of the reasons why I’d gone, was because one of our star jumpers was a woman – and there weren’t very many women in the parachute at that time – this was in the late 1970s. And because I just started parachuting myself, I thought I could do a couple of jumps with the team. And they were quite keen to do that because it sort of put me in the heart of the action.

On the first jump I did, I was using a parachute that I was unfamiliar with, packed not by myself but by one of the other parachutists. And I always pack my own parachute, that’s one of the secrets of successful parachutists: pack your own chute – you take a lot more care of it. When I exited the aircraft, which I was unfamiliar with, I think I jumped out at about 5,500ft, went to pull my rip cord, nothing happened. It was jammed, I was struggling trying to open it. The instructions they give you are: if you can’t do it, pull your reserve. Give up and pull your reserve. But I wasn’t prepared to do that. I wanted to get my big parachute opened, so I kept pulling and pulling and pulling it, until finally I gave up and pulled my reserve at 700ft, which is like three seconds before the lights go out, because your terminal velocity is 125mph. So you’re falling quite quickly. You haven’t got time to make quick decisions. And if you don’t make a quick decision, you haven’t got any time anyway. It was just one of those things. I fractured my ankle, I came back to work, got castigated by my news editor because I was told not not to take part in parachuting, because how could I resist?

FT balloon ready for take-off in front of St Basil’s Cathedral in Red Square

FH Going back to ballooning, what is it that you love about ballooning? Is it the silence?

PM The tranquillity, the fact that you can float quietly, silently over the countryside. You can have a conversation with people, you don’t have to shout. You have to put the burner on occasionally of course, to keep the air inside the balloon warm. But it’s like a constant noise, it’s not like a small aeroplane with the engine running all the time. You’ve got a burner on permanently when you’re in the balloon. And so you’ve got little bursts of 5 or 10 seconds and then 30 seconds or a minute of silence. And that is lovely. Also being in the open in a woven wicker basket. It’s just a wonderful feeling of freedom.

PH Peter, where were you born?

PM Born in Melbourne in Australia. I’m a sixth-generation Australian, born and bred. My parents were both Australian journalists. Our family moved to England when I was 15 and I think that the main consideration in my parents’ mind was that they wanted to escape the stultifying dullness and provinciality of 1950s Australia. They did what many had done before them and have done since – people like Clive James, Germaine Greer, Barry Humphries, Robert Hughes – the art historian, they all left Australia in the late 50s and early 60s, at about the same time we left to come to England, because they wanted a new life. They wanted to get away from what Australians jokingly refer to as ‘the cultural cringe’. And in a way, I guess it was a bit dull in those days. Australia is a different place altogether now. It’s vibrant, lively, very culturally inclined, and it has some of the best restaurants in the world. It has theatre, it has the Opera House. It’s changed radically since I left in 1958.

PH So what made you go back to live in Australia after all these years?

PM I suppose because it was my home. In fact, the real reason is because in 2000, I was diagnosed with leukaemia. We were living in Cornwall then and running our business quite happily. And a few months after that diagnosis, it was found that I had renal cancer and I had to have a nephrectomy – had my left kidney removed. Because of the two things in tandem, the prognosis wasn’t good and they thought I might have five years. I’d been given a timespan. We didn’t know how long I was going to be. And here we are, 20 years on, I’m still here.

PH And hopefully for many more years to come. Peter, thank you for chatting to us today. I should just add that I have actually been up in a balloon piloted by you many years ago, and it was indeed a truly remarkable experience.

FH That’s all for now. If you’ve enjoyed the show, please share this episode with at least one other person! Do also subscribe on Spotify, i-Tunes, Stitcher, or any of the many podcast providers – where you can give us a rating. You can also find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Stay safe and we’ll see you next week.

© Action Packed Travel

- Join over a hundred thousand podcasters already using Buzzsprout to get their message out to the world.

- Following the link lets Buzzsprout know we sent you, gets you a $20 Amazon gift card if you sign up for a paid plan, and helps support our show.