Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter Welcome to our travel podcast. We’re specialist travel writers and we’ve spent half a lifetime exploring every corner of the world.

Felice So we want to share with you some of our extraordinary experiences and the amazing people we’ve met along the way.

Peter This week we’re at Bletchley Park, the country mansion 35 minutes by train northwest of London, where Alan Turing and his team of cryptanalysts cracked the complicated codes of the German Enigma machine.

Felice They were helped by the forerunner of the earliest computer that they built here to speed up the process from weeks to just hours. Their work heavily influenced the outcome of World War II and possibly helped to bring about Allied victory. The Oscar-winning 2014 movie, The Imitation Game starring Benedict Cumberbatch, tells some of the story of what happened here back in the 1940s…but that’s by no means the whole picture.

Peter Failure to discover the existence of Bletchley Park and what went on here between 1939 and 1945 proved to be the greatest error of the entire Nazi war machine. This was the intelligence-gathering nerve centre of the Allies and it operated on a grandiose scale. By the end of the war, some 9,000 people worked here in top secrecy in a series of huts built in the 50-acre grounds of the mansion. Their job was to supply Turing and the codebreakers with encrypted radio messages hacked from German and Japanese and Italian radio communications all over the world.

Statue of Alan Turing in theIntelligence Factory exhibition. Photo: © F.Hardy

Felice The Intelligence Factory is the name of a fascinating, hands-on exhibition that’s recently opened here at Bletchley Park. We met up with chief organiser, Peronel Craddock, to tell us all about it. I should just point out that the interactive displays and Turing’s electromechanical machines are quite noisy.

Peronel The Intelligence Factory is the largest permanent exhibition to open at Bletchley Park, and it’s a really important story for us. It tells quite a hidden history that was actually really, really important to the impact that the site’s work had on World War two. Bletchley Park is obviously known for Codebreaking. It was the home of the codebreakers in World War II, but what is less known is its function as an intelligence organisation. In fact GCHQ today is the organisation that was at Bletchley Park in World War II. So there’s a really long history of intelligence generation and that was the key point behind what we wanted to get across in the exhibition.

Peter We’re going back to a world where there was no computers. That’s essentially the difference between now and GHQ today isn’t that?

Peronel That’s quite right. Everything today is, of course, digital and enormously quicker than it would have been in World War II. So the codebreakers had a huge challenge on their hands. The importance of the intelligence coming out of Bletchley Park had really proved its worth in World War II, but where we pick the story up in 1942, there was a huge demand for this, and that meant that the whole site and then the work that happened here had to scale up very, very quickly to meet that demand. There were mountains and mountains of intercepted messages coming in. Those had to be decrypted and they had to be indexed and analysed and turned into this incredibly concise, digested intelligence that was of proper strategic importance to Allied commanders and to commanders in the field.

There were 9,000 people in Bletchley Park in its outstations working around the clock, so 24/7. There were three shifts at Bletchley Park on site, eight hours each, and the whole process moved from a fairly cottage industry through to a proper factory of intelligence generation, where the work was broken up into lots of different stages or carried out by different teams working independently of each other but as part of this enormous whole.

Peter Presumably the logistics involved of having 9,000 people…were all civilians or half civilians?

Peronel They were recruited from pretty much anywhere they could find in wartime. We did have quite a lot of civilian staff working here that were recruited through the Foreign Office. But we also had many, many staff who were with the women’s services and in the services in general.

Listening devices. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter The listening was done elsewhere, presumably?

Peronel the listening was done in the WI stations – those are wireless intercept stations based around the UK and also globally. So their job was to listen in to wireless signals sent by the enemy and write down whatever they heard. It would have been transmitted in Morse; what came out of the Morse was encrypted.

Felice Everything is decorated in the same colours.

Peronel Yes. So this project was the most amazing opportunity to restore Block A – the first of eight brick blocks to be built on the site – to its wartime appearance. And so we worked really carefully with our conservation architects, and we’ve done research into the building’s history, including paint sampling, to be able to recreate exactly what the building would have looked like right down to the colour schemes and the type of lighting and blackout blinds, how it would have been in World War II when the codebreakers worked here.

Peter Tens of thousands of messages came in all the time and they were transmitted in Morse to here where they were printed out, presumably. And then what happened?

Peronel They would have come into the codebreakers as encrypted message materials. So it would have looked just like gobbledygook – sets of five, four letters that made no sense at all to the reader. That was the raw material the codebreakers were working on. Their first job would have been to break the encryption and to read those messages. They didn’t look at every single message that came in, because the volume was enormous. So there was a constant communication with Allied command about what was at most interest and importance, and they would then focus their activities on certain sets of messages or certain areas of the war.

Those individual messages, each one of those contained a crucial piece of information, sometimes a very trivial piece of information. But the scaling up of the work enables them to build an enormous index of all of these individual pieces of information. It was actually being able to cross-reference and give context to each individual message that made the intelligence so useful.

Photo: © F.Hardy

So we had teams of intelligence analysts working with the index material, understanding not just what they were seeing on that particular transmission, but what that meant for the course of the war, what that meant for the Allied strategy, and then sending out the Intelligence Digest that they produced from the information to other intelligence organisations, to Churchill, to Allied commanders, and straight out to the field as well, where they could be put into operational use. And that had an impact on every sphere of the war across the globe. We weren’t just focusing on German codes and ciphers – we were focusing on Japanese and Italian and influence in the war in the Pacific, as well as the war in North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the war in Europe.

Peter Logistics of handling these 9,000 people were really quite remarkable. I saw on one of the wall charts, I can’t remember how many meals per day, but I mean, quite an extraordinary number, just to get the people billeted presumably it was difficult? I mean, 9,000 people in what was then very much countryside to find places within easy distance was it?

Peronel It was an enormous undertaking and pretty much everything was brought to bear on trying to make sure that they had all the resources in place to support – not just the work, but, as you say, the life and the how to feed people, where they’d sleep, how they got to work, all of the logistics and operations that go into that. We’ve got the most wonderful repository of memos done at the National Archives in London that really go into the minutiae of the daily life. And we’ve been able to reproduce quite a lot of them in the exhibition to give a glimpse into what it was like to feed people, to find enough accommodation, even down to where you sourced rubber tennis balls.

Felice There wasn’t any accommodation here, was there?

Peronel That’s absolutely right. None of the codebreakers were accommodated at Bletchley Park itself, there simply wasn’t space on the site. So at the start of the war they were using local inns and hotels and private houses. People would be billeted with local families. Later on when the site grew and grew, purpose-built camps sprung up, they took over large country houses like Woburn and Wavendon, they billeted lots of people there. They were being brought in by bus or coming in on bicycles or in private cars. Many forms of transport, sometimes after dark in the blackout, which must have been an adventure in itself.

Peter But I read here that 25,000 miles a week was the total mileage by the taxi service of bringing people to and from work.

Peronel Yes, absolutely. And the people were the bread and butter of the organisation. Every person was one of the little parts of the whole factory process. Their work was needed to carry on.

Felice This must have been a potential target, though, for bombing?

Peronel Well, the purpose of the site itself was entirely secret. Everyone who worked here had to abide by the Official Secrets Act and were not allowed to talk about it even between themselves, if somebody worked in a different part of the organisation. But while it would have been obvious to people around that there was something going on here, this type of military establishment was springing up all over the country as part of the war effort. So in a certain sense it was nothing out of the ordinary to a casual observer. It’s only when you know of the important work that happened here that it suddenly becomes much more important. So because that secret never got out, the site was never actively targeted. I think the site was bombed once, but it was accidental, it was a bomber coming back from a raid, just jettisoning and it hit one of the huts here. But apart from that, no, it wasn’t targeted.

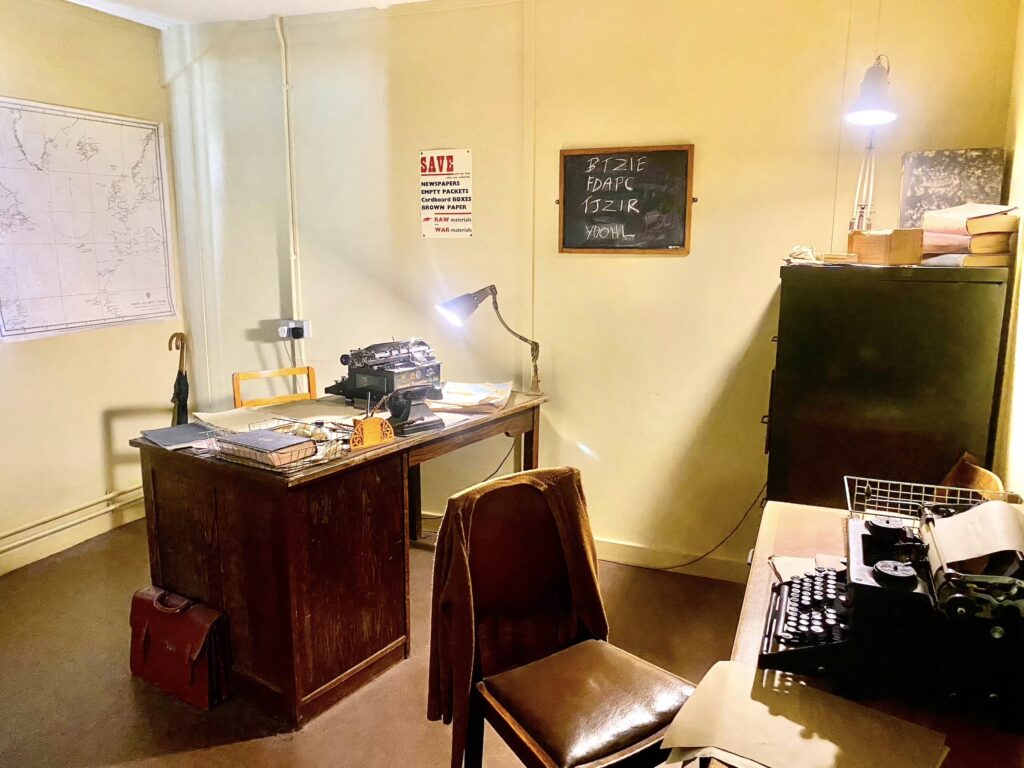

Alan Turing’s office in Hut 8. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter It’s very remarkable, really a failure of intelligence.

Peronel I find it completely astonishing that somewhere that employed so many people and was here for such a long time, all the way through the war, doing such work could have been kept secret. I mean, in our present day, it seems almost inconceivable. But it worked, the people here did keep very, very quiet about it, and in fact, some of them still do.

Felice When did Bletchley Park first open?

Peronel So Bletchley Park was chosen as the wartime home of the Government Code and Cypher School, who had been based in central London. And it was purchased just before the war broke out by Admiral Sinclair, who was head of SIS at that point. It had various advantages. It was very close to a massive communications hub, and of course communications were key to the work here, as well as good transport links and the rest of it. So the codebreakers first moved up here in 1938 when it felt that war might be imminent and they had essentially a trial run. It came up and were running their operation from here for a few weeks. Things settled down and they went back to London.

But then when we got to September 1939 and war was absolutely on the cusp of breaking out, they came up here the day before and they were up and running within a matter of hours – just carrying on their work as usual but away from central London and its targets. It was only a couple of hundred at the start; the organisation itself had been formed just after World War I, bringing together the signals intelligence units from all of the different forces and the Foreign Office and combining them into one. They had been working on various problems; they’ve been working on Enigma, for example, through the Spanish Civil War. So there was a lot of knowledge and expertise there, but only a few hundred people.

Felice The visitors today, apart from the exhibition, what other things should they go and see here? Because there’s a lot, isn’t there?

An office in the mansion. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peronel There is a lot to see at Bletchley Park. We’ve got a beautiful site with lovely grounds, so we recommend people come and spend a day with us. We tell the chronological story of the codebreaking on site between 1938/1939 and 1946, when the organisation left this site and we tell it in the place where it happened. So you can visit the mansion, which was the first place that the codebreakers set up their offices. Find out about those very early days and then explores the as the site grows, as the story gets bigger through the codebreaking huts and then into the blocks where we have the Intelligence Factory.

Then we have other exhibitions that give a glimpse into the context and the impact and the relevance of their work today. So, for example, we have a temporary exhibition on the Art of Data, which talks about how we visualise data today and the techniques we use to manage and interpret masses of data, which is so much parallel to what was being done at Bletchley Park, particularly in places like the Naval Plotting Room, which we’ve managed to recreate in the Intelligence Factory.

We also have a large exhibition on D-Day that really brings home the impact of Bletchley Park’s intelligence on the success of the D-Day campaign. That’s a massive, immersive film; it takes you out of the site and into the war. Of course, we have a lot here on Alan Turing who was a very famous name among the Bletchley Park breakers and his and the team behind the Bombe machines that were developed to help break the Enigma codes much more efficiently and more quickly than they’d been able to do by hand.

Felice When people arrive, is there a map they can look at so that they can find their way around?

Peronel Yes, we have a map available. In fact, before your visit, our website has a lot of information about what there is to see, so you can pick and choose. We have maps available to everyone at reception. We also have multimedia guides, which are included in our entry price, that take you around the site. We have amazing team of volunteers who run tours that you can just drop into. Again, that’s included in the entry price and that’s a fantastic overview for anyone who hasn’t been before. It takes you through the main story of the site, it takes you around the key buildings, and it’s a really great starting point to then explore a bit more deeply yourself.

Peter Well, I think we’d like to come back here in a minute, but can we go and take a look at the Enigma first of all.

Peronae Certainly.

Peter So give us a quick summary of Enigma and what Enigma is, to people who don’t know?

Bombe breakthrough. Photo: © Bletchley Park

Peronel So Enigma is a mechanical and ciphering machine is an electromechanical and ciphering machine. And it works by essentially scrambling the letters of a message using a system that was considered initially to be pretty much unbreakable. So the Enigma machine itself has a keypad on it that looks a little bit like an old fashioned typewriter. Behind that is another set of alphabet that light up, letters that light up, called the lamp board. So when you’re typing your message in, you type it in plain text. Every time you type a letter, a letter will light up on the lamp board, which will be your encrypted letter. So you might type in P and it might come out as Z and so on. And the Enigma encryption works on a very sophisticated system, a key that is a combination of settings, pre-set settings from a sheet that you can just read off and then another part is the setting that they come up with themselves and add into the encryption. So they would adjust the machine’s settings before they start to meet that day’s key, and the person at the other end would set their machine up in exactly the same way. Then if they typed in the encrypted message, they would get the plain text out of it.

So the machine did the encryption, the messages would be sent by wireless transmission using Morse code, they’d be written down at the other end, plugged back into an Enigma machine, and there you go. So what the listening stations – the Y service – were doing was intercepting the radio transmissions of those messages. So they could hear those Morse letters being sent across the airwaves, they would be writing them down. So as that message was getting to its intended recipient, it would also be written down by the British and sent back to Bletchley Park.

Alan Turing joined Bletchley Park pretty much at the start of the war. He was recruited from Cambridge University; he’d been on a list of likely people that they were thinking would be helpful to call up if war broke out. He was set to work on Enigma with many, many other codebreakers. The Enigma unit at the start of the war was led by Dilly Knox, who had been working on Enigma for some time, particularly in the Spanish Civil War. We have a machine on display here that is a Spanish Civil War Enigma machine.

There was some knowledge of the Enigma cipher already, but also the really key part of knowledge transfer came from the Polish who, just before Poland was invaded, called a conference in Poland, invited the British and the French codebreakers to that, and shared what they knew – because they had also been working on Enigma for many decades.

Enigma was initially invented in the 1920s as a commercial machine – because it had this potential to be militarily, strategically important, codebreakers in various places had been already working on it and looking at it and trying to understand what lay behind the encryption. So the British were fortunate to receive a lot of existing knowledge that, coupled with their knowledge and the new ideas coming in from everyone that they put in to bear on the problem, allowed them to get a real head start. I think it’s probably important to say that there was no one Enigma machine; there were many, many models, and it was a little bit of an arms race. You know, the machine itself started to get increasingly more complex, techniques became obsolete, and you had to think of something completely different.

Peter What about the Bombe machine. I think this was an early type of computer invented by Alan Turing and his team. What was the function of it?

Peronel This essentially allow you to crunch through many, many, many, many different combinations of potential encryptions to find ones that would match. So it was a massive breakthrough in the decryption of Enigma. It allowed them to potentially find a key in as little as 12 minutes, whereas doing it by hand could have taken several days.

The first Bombe was produced in 1940, again drawing on all the knowledge at Bletchley and the knowledge shared by the Polish, Turing was able to come up with the idea of an electromechanical machine to help speed up the process. It took a bit of time to get the prototype perfected. But by the end of 1940, quite a lot of Bombes were already in operation and the numbers just increased through the war. It just gave the codebreakers the potential to read so many more Enigma messages. They were vitally important because they were carrying the on-the-ground operational information from German units. Each German unit in the field would have had an enigma machine with them, and it was how they transmitted all of their communications. So it’s that vital on-the-ground operational information that could come from Enigma.

Peter We were hearing it on the airways between the front line and Berlin, for example?

Peronel Precisely. Yes, exactly. These were the sort of orders and the status reports from all of the units engaged in combat, or being moved to different locations. And all of that information could help build up a picture of the German strategy and German operational movement.

Peter So when do they actually break the code?

The Intelligence Factory. Photo: © Andrew Lee/Bletchley Park

Peronel So the first breaks in Enigma at Bletchley Park were in early 1940, late 1939, but they were breaking it by hand. So by the time they got into the messages, they were a little bit out of date. Doesn’t mean they were useless, because obviously all that information gives you a really good picture of what was happening. But when the Bombe machines came in because they speeded up that process so quickly. We’ve got examples of, for example on D-Day – on the day of the invasion itself, we were getting from intercepted message to completely translated plain text English message in as little as three hours.

Peter It’s amazing. And that certainly changed the war.

Peronel It had a huge impact on the world, just the amount of information that could be then passed as intelligence out to Allied Command and give them an insight.

Peter I should just explain that the Bombe machine we’re standing beside has just come to life.

Peronel Yes, we can see the rotors turning, kicking away. And yes, it makes this wonderful thunking noise.

Felice Would messages come through from resistance and other people, British, working in Germany, places like that?

Peronel So Bletchley was only concerned with messages sent by the enemy. They were a partner organisation to the other intelligence services who would have been dealing with messages from agents in the field, British agents in the field, but they were absolutely sharing information. Again, particularly with D-Day, all of the intelligence that helped inform the invasion tactics came not just from Bletchley, but from a whole range of other sources, including agents in the field, from the Americans, from aerial reconnaissance, from every potential source. That was all digested here into the intelligence that was needed to help plan.

Peter And we worked closely with the Americans, presumably?

Peronel Very, very much so. We called Bletchley Park the birthplace of the special relationship, because that began as an intelligence-sharing relationship and the initial agreements were signed here in the mansion.

Felice You also mentioned Poland was involved somehow.

Peronel Poland was really key to Bletchley Park’s knowledge of Enigma. They weren’t starting from scratch here, they were building on knowledge from their own efforts with Enigma, pre-war, and from a large amount of knowledge that the Polish shared just before they were invaded by Germany. They handed over everything they knew, incredibly generously.

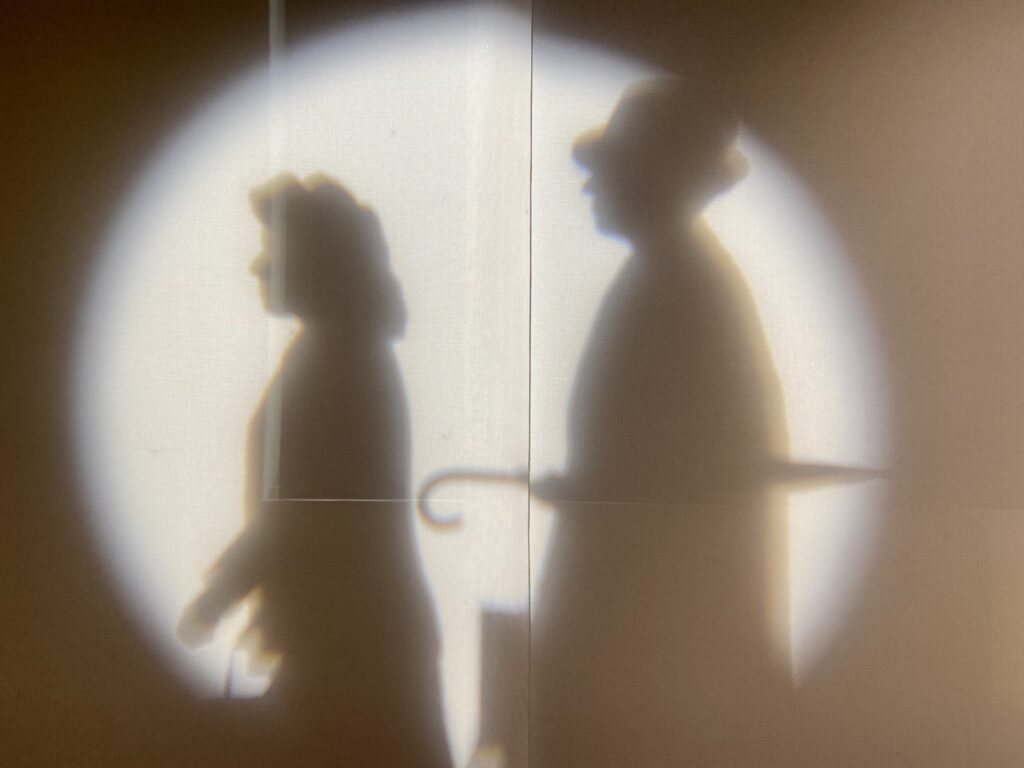

Peter The old Royal typewriter and the telephones. It actually is rather a long way from computers.

Peronel It’s very far from a modern office, isn’t it? And we have got a set of very few photographs of the mansion in its earliest days.

Felice So who do you think would enjoy coming here for the day?

Peter Well, I think almost anyone. I think some of the schoolchildren are still going around were too young to appreciate it. But the ones who are 12 and upwards were fascinated, clearly fascinated, because this is after all really the birthplace of modern computing,

Felice …and radio, television. There are different exhibits, but large. Each one is a mini museum in its own right. So there’s information about television, radio, how they started, computers, and then there’s a whole section on the future and how everything here influences it.

Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter You can walk around, I mean, literally dozens, perhaps scores of rooms which have been done up in the style of the 1940s, with old typewriters and overcoats hanging on pegs.

Felice You say the word ‘overcoat’ wisely.

Peter Well, that’s what they were, overcoats hanging on pegs, one with remarkably ‘Harris Tweed’ written all over it. Then there’s umbrellas, tere’s a bike rack outside full of 1940s bikes.

Felice Crocodile handbags.

Peter Oh, I didn’t see that.

Felice I saw one.

Peter What else was there? Is everywhere warning you to keep your mouth shut ,to not discuss what went on here. And perhaps the most remarkable thing of all was the German Abwehr, the biggest failure of intelligence was they never discovered Bletchley Park or what went on here.

Felice You really do need a whole day, and there’s a station within walking distance, so it’s quite convenient. If you want to know more about Bletchley Park and the Intelligence Factory exhibition, go to BletchleyPark.org.uk

For further travel information on where to stay, shop and eat either before or after your visit, go to ExperienceOxfordshire.org

That’s all for now. If you’ve enjoyed the show, please share this episode with at least one other person! Do also subscribe on Spotify, i-Tunes or any of the many podcast providers – where you can give us a rating. You can subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or any of the many podcast platforms. You can also find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. We’d love you to sign up for our regular emails to [email protected]. Until next week, stay safe.

© Action Packed Travel

- Join over a hundred thousand podcasters already using Buzzsprout to get their message out to the world.

- Following the link lets Buzzsprout know we sent you, gets you a $20 Amazon gift card if you sign up for a paid plan, and helps support our show.