St Brelade’s Bay. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter We’re specialist travel writers and we’ve spent half a lifetime exploring every corner of the world.

Felice So we want to share with you some of our extraordinary experiences and the amazing people we’ve met along the way.

This week we’re in Jersey in the Channel Islands, best known for its beautiful sandy beaches, low taxes and delicious new potatoes, as well as being the only part of Britain that Hitler managed to occupy during World War Two.

Peter Now, Jersey is the largest of these Channel Islands. It lies some 87 miles south of the English coastline, but only 14 from France. However, while English speaking Jersey is part of the British Isles. It’s not part of the United Kingdom and has never been part of the European Union.

The island is self-governing and it only relies on Westminster and the British Parliament for its defence. Not that it had much success with that in the dark days of the 1940s, when the Germans invaded the islands. Faced with the impossibility of defending Jersey and the other islands, Churchill and the British War cabinet in 1940 voted to leave the islanders to fend for themselves.

Felice Nazi troops turn the island into a fortress studded with gun emplacements to defend nearby Saint Malo and the French coast. It was important for Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, 1670 miles of coastal defences that stretched all the way along the boundary of mainland Europe – from Scandinavia to the Spanish frontier. It was designed to resist any Allied invasion.

Peter So what happened to the islanders during the war years under Nazi occupation? We went along to Jersey’s capital St Helier to find out. Our guide Nicky, filled us in as she gave us a lightning tour of some of the crumbling coastal defences linked by a network of underground passages – and even an underground German hospital.

Jersey’s Slave Workers’ Memorial seen through a gun slit at St Ouen’s Bay. Photo: © F.Hardy

Nicky So now we’ve got a view right the way across St Ouen’s Bay to Elizabeth Castle. I think the interesting thing about a lot of things in the island is you’ve got layers of history. So Elizabeth Castle, you’ve got a little chapel on it, which is from about the 10th century. There used to be a monastery, it’s an Elizabethan castle. Then you’ve got Georgian things in it, and then you’ve got German occupation things on the top of it. So you get these layers of history within the buildings.

Peter How large is the island?

Nicky It’s nine miles by five and it’s got 106,000 people living here now. When I came to the island 40 years ago, there was 82,000, so it’s grown quite considerably really.

Peter During the occupation, were there are lots and lots of Germans here?

Nicky Before the occupation, there was about 50,000 people. The war had started in 1939, and just before the Germans occupied quite a number of people evacuated off the island.

Peter When did the Germans actually arrive here?

Nicky So they arrived on the 1st of July 1940. They’d bombed fairly close to this area. They did come in an air raid. Basically the island was demilitarised, but the Germans didn’t realise this. But the Germans thought it was and there were potato lorries along here. They thought they were military lorries, and in the end they bombed this area. But ten people, I think it was, who died.

Peter Do you know how many German troops there were on the island?

Nicky There were about 40,000 local people and then about 12,000 troops. I mean, it did change during the war. But then also there was another…possibly up to 8,000 or maybe more…workers who were brought over to build the bunkers and build the sea walls and build all of those sort of things.

Peter So the Germans came in quite aggressively, or was it quite quiet to start with?

Guns at above St Ouen’s Bay. Photo: © F.Hardy

Nicky It was very quiet, really. I mean, they literally landed at the airport. They dropped notes to say that we had to surrender, and people had to put out white things on their roofs. I mean, there’s stories of people putting their vests and pants up on the roof, white sort of things, just so that they could show that they surrendered. And then the next day, after all these white things were hung out, they literally landed at the airport and arrived. It was a big propaganda thing for them because there’s some classic photos of German soldiers next to Woolworth’s and an English policeman – or Jersey policemen.

So this is the Ommaru Hotel; this was the brothel during the occupation. A very sad thing that a lot of prostitutes were brought over from France and then they were going back on a boat and the boat actually sunk. There was quite a tragic event. So, yes, this was this was where the lorries were – it’s now called Liberation Square actually, this is here. And there’s a there’s a statue in the middle showing the liberation. So when the island was liberated, this was an area of great celebration.

But the building that we’re passing is actually the old abattoir and market area. And so the potato lorries were all lined up along here and that was the area that was bombed.

Felice After the first few weeks, did it get a bit tougher for the islanders?

Nicky Yes, to begin with. I mean, basically the bailiff of Jersey, Alexander Couzens, he did remain in control of local affairs. I think he did a very good job of being a mediator between the German occupiers and the local people. But gradually, as the war came on, there were more and more regulations put in. To begin with there was still lots of stuff in the shops, there was still food and everything here. There wasn’t any major shortages of things.

So in fact the Germans, apparently when they arrived, they went on a bit of a spending spree in the shops because they hadn’t had that sort of stuff at home. But yes, as time went on, it got harder and harder really.

Where we’re heading to is the headland, which you can see off to the left there and that’s called Noirmont. And there was a very large strong point on that area. So there would have been a lot of busy soldiers. Well, it was actually the Navy who were there and there would have been garrisons up there, but the officers tended to be in the hotels and lodging houses, and some people had to take in German soldiers.

Although the bunkers were built to be able to house people, often they weren’t actually living in them. But you’ll see that there’s just an enormous amount of concrete poured into the island and that was really all from about 1941 to about ‘43. It’s only really two years of building, and it’s incredible how much they did in that small amount of time…when you look at how long buildings take to be built now.

Peter Did the Germans deport quite a lot of people from the island?

Nicky Yes, I think it was in 1942, anybody who had English ancestry, they were deported to Southern Germany. And there was about I think it was about 1,200 evacuated. They were taken off the island. It was a camp. They lived a fairly normal life. Well, as normal as it could be. I mean, they were housed in a very large castle type place.

Peter And they were interned essentially?

Nicky Yes, that’s right.

Peter The Jews on the island…were there many Jews?

Nicky Well, there were some Jews. I mean, all the Jewish shops were closed. They were part of the internment. They weren’t sent away to concentration camps from here. There were two different things happening, really. There was the internment, but also some people were sent to prison for having a radio perhaps, or doing something against the Germans during the occupation.

There’s one story about Louisa Gould, who was a really interesting lady. She lived out in St Ouen’s and she actually protected a slave worker for a long time. And he became part of the family really. The classic saying that she had was ‘I’d wanted to look after another mother’s son,’ because her son had died in the war and she wanted to look after this person. But she got informed on and ended up in prison here, and then she got sent to Ravensbrück and she died in Ravensbrück. But her brother also went and he actually was one of the very, very few people who came back from Belsen. He was actually there.

So yes, there’s quite a number of those stories of people who were sent away. There’s a memorial near the Maritime Museum for all the people who were sent to concentration camps. I think there’s about 20-odd names on it.

Peter Presumably, in terms of survival, food in particular…conditions got more and more difficult as the war went on?

Nicky Yes, the hardest thing was basically after D-Day it became much harder. The supply lines for the Germans and the island were cut because obviously we’ve got France on two sides of us and everything was being brought in from France, which was fine.

Once France was liberated, then there was no food coming in. So that was a really, really hard time, not just for the Jersey people, it was also hard for the German troops as well. You know, there was lots of talk of eating limpet stew and making coffee out of ground acorns, and, you know, there’s lots of stories like that.

“Dedicated to the thousands forced to labour for their persecutors 1940-1945.” Photo: © F.Hardy

“Felice The slave workers that you mentioned, were they taken from concentration camps in Poland and places like that?

Nicky Well, I’m not sure where they came in from – Poland, from Ukraine, there were Russians. It’s interesting, there was probably about 11,000 or more workers brought in. Some were slaves, so that was the Russians – and the Germans would call them the Unter Menschen and the real bottom of the in terms of people.

But then there were also Spanish people brought in, there were some Belgians, so there were some forced labourers, there were some paid labourers and Jersey people. Also some Jersey people did end up working on the building of all the different bunkers.

The Russians apparently and the Polish were the ones who were treated the worst, really. And, you know, people talk about how they’d see them being taken to work and they’d try and throw them a turnip or something, or throw them something to eat and try to help them a little bit.

So we’re now coming on to the headland, which is called Noirmont. It’s almost like a peninsula sticking out. And this is where the German navy were. You’ll see…there’s…I don’t know how many bunkers there are here, but a massive number of bunkers. There’s a big what they call the MP towers, which were range-finding towers and all concentrated onto this one thing. And they almost seem a bit like being on a boat really.

Peter From the moment when the Germans first landed, there was actually no contact with England at all until liberation?

Nicky No, that’s right. I mean, they had Red Cross letters which would come in. Some commandos did land at a place called Egypt on the north coast just to see what was happening in the island. But that didn’t really work very well. There was a little bit more of that going on in Guernsey, because obviously Guernsey is that much closer to Britain. And so they did have a few more people coming to try to find out what was happening in the islands. But they were really basically left to their own devices.

Peter So was there a feeling amongst the islanders that they’d been abandoned by Britain?

Nicky Yes, I think so, definitely. It was taken fairly badly really, I think by quite a lot of people.

Peter Well we’re on a very remote headland here and there’s all kinds of old concrete bunkers and lookouts. It must have been a very bleak sight in 1940.

Felice It looks a bit like Cornwall, actually. Land’s End.

St Ouen’s rugged coastline. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter We move on to the little village of St Brelade, which is just along the coast from St Helier.

Nicky This was called the St Bernard’s Bay Hotel. But during the occupation, this is where the officers stayed. And it was almost like a recuperation. People could come, were brought in here from elsewhere and they could actually stay. It was like a place to recuperate really.

Peter On the sea side.

Nicky Yes, absolutely. So in the house just behind us here, and that’s where Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore lived. And they were a fascinating pair. They were French artists. Their proper names were Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe, and they came over in about 1936 to live on the island. They were a couple, but they were also step-sisters so at the time it was acceptable that they were living together in this house here. They were surrealist artists. Claude Cahoon was a photographer who developed lots of techniques of superimposing pictures on top of each other and all sorts of different things. And there’s an amazing collection of her photos in the Jersey Museum.

During the occupation they became resistance fighters in a way. But it was all very passive resistance. So they had a radio and they used to listen to it. They spoke German, so they were able to translate what was happening in the war into German, and they were typed it up onto little notes which they put into Germans’ pockets and, and to try to destabilise things, really, to tell the Germans what was happening in the war – actually happening rather than the propaganda which they were hearing.

This went on for a long time. And in the German cemetery, which was in in the church here, they used to put black crosses on the German graves and a number of small little acts of resistance, really. So they were a fascinating pair.

Lucy Schwob and Suzanne Malherbe’s Jewish headstone in the church graveyard. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter And all the time with their radio set, they were living, what, just ten meters from the German officers’ hotel?

Nicky Absolutely. They were living very dangerously, but they’d look like two very ordinary middle-aged women. And they really were not that at all. They were really quite an amazing couple.

Peter So what happened to the pair of them?

Nicky Well, they did eventually get caught having a radio, and they discovered that they’d written all these notes. And so they ended up in the local prison. They were given the death sentence actually, Claude Cahun, she’s alleged to have said she got a death sentence for all the notes and things and she got a prison sentence for holding the radio. And I think she said, ‘You know, which am I going to get first?’ The story is that they did try to commit suicide in prison.

Felice Did the Germans shoot any Jersey people?

Nicky I think there was one or two executions. But because people couldn’t resist in a way, because if they did resist, there’d be such reprisals In this area around La Moye, where we are now, the forced labourers were in a camp here, and there’s a great story about a Belgian worker. He was working on the walls and he met this young girl from La Moye, a local girl, and he got sent back to Germany. And the story is that he actually ended up escaping back to the island to be with this girl. So he was the only person to actually escape into the island during the occupation.

He’s only fairly recently died. He was the grandfather of one of my daughter’s friends. Apparently he went down to one of the bunkers on an open day and they said, ‘That’ll be £5’ or whatever to come in. And he said, ‘Well, I’m not paying because I helped build it.’

So we’re now down on the headland of La Corbière, can see the lighthouse just off to the left there. And we’ve also got a second one of these control towers, which you can see. This one’s quite interesting because it used to be Jersey Radio, the coast guard used to be from here, which is why you’ve got the glass roof on it – but now it’s actually somewhere which you can rent to stay in.

Jersey Heritage rent it out to stay in, and it’s an amazing place. It’s got three double bedrooms and it’s got a kitchen, and then the lounge is the top which just gets an amazing 360 degrees view.

So I think one of the amazing things you’ll notice that every single headland has got concrete on it – bunkers and you’ve got the sea walls. And the thing that always I find really interesting is just the thought that every single bag of cement which they used, had to be brought into the island because there’s no local cement. There’s been a calculation done that it was over a million bags of cement had to be brought in. So apparently 250,000 tonnes of cement had to be brought in to the island from Germany, and it was 40 million man hours they calculated in the building of all the defences.

Peter Remarkable isn’t it?

Nicky The fact that it was done in such a short period of time because they didn’t really start doing the building until slightly into the war, they’d been here about a year or so before they started. And so it’s a huge, huge task and often having to build through granite…so incredibly hard labour that it was happening here.

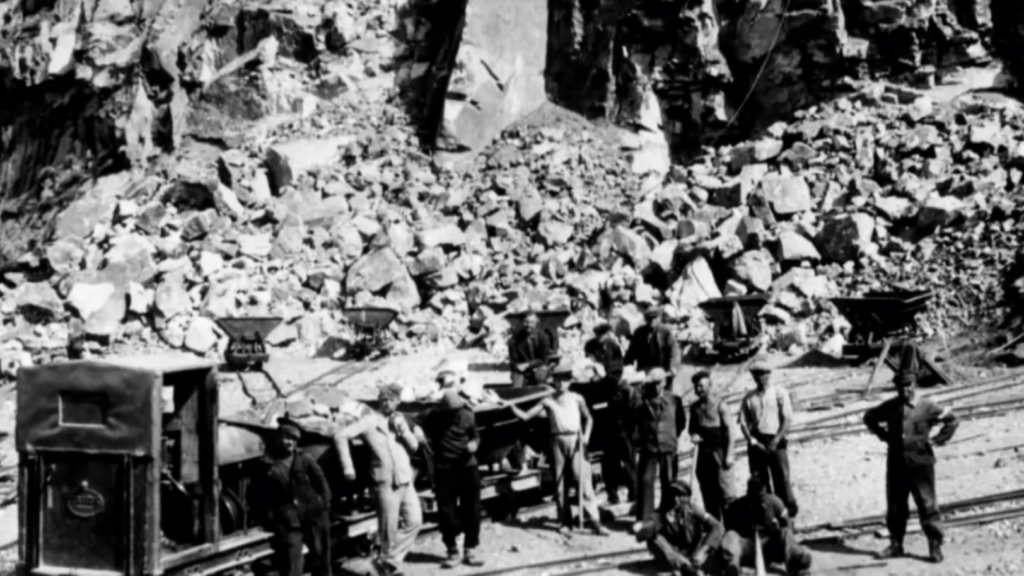

Slaves working at Ronez Quarry in St John. Photo: Société Jersiaise

Peter Where did the slave labourers live?

Nicky They were various camps around the island where they lived and often they, they worked all week, but then they sometimes had Sundays off, but then on the Sundays when they didn’t work, they weren’t fed. So they would then go scavenging around trying to find food and things. So I think it was really tough. I mean, there were different types of labourers, you know, it wasn’t all slave labour. It was also some forced, some paid labour, some Jersey people.

Felice The slave labourers…were they fed properly? The slave labourers in Poland and places like that weren’t fed, they were starved at the same time.

Nicky Yes, I think pretty much the same here. I think they would have had the bare minimum of food to keep them able to work, really. Alderney was in a worse position; it pretty much had something similar to a concentration camp on it. It was evacuated totally. It’s got a fairly bleak history during the occupation.

Peter Certainly after D-Day, the people who suffered most with the slave labourers.

Nicky Yes. But by that time, most of that that the building had stopped then and they went, and after D-Day it was the locals and the German soldiers. And in fact they were saved pretty much by something called the Vigo, which was a boat that came in – a Red Cross ship that brought Red Cross parcels in. And that happened just after Christmas 1944. People say that was what saved them, really.

As we come along this section here, this is St Ouen’s Bay. The whole of the bay has got tank defence, sort of walls all the way along and you’ll notice in the sand dunes and things, there’s lots and lots of bunkers hidden away along the whole stretch of this coast. Because this is the West Coast and obviously this was a first port of call. If an attack came, people believed that this would be where it was.

You can see out in the bay one of the Jersey round towers, which were the earliest sort of 1780s, they were all built against the French.

Peter So, Nicky, can you just explain what Jersey’s relationship is with the United Kingdom?

Nicky We’re what’s called a crown dependency. So what that means is we have allegiance to the King now, but we don’t have allegiance to the government. Royalty to the Channel Islanders? The Queen was our Duke. The King is now our Duke because we were part of Normandy when William the Conqueror conquered Britain. So we were on the winning side at that point. And there were Jerseymen was fighting alongside William the Conqueror – he was our Duke. When the French lost us, basically King John lost a lot of his French land and Jersey almost had an option to become part of France or to stay with Britain.

Peter 13th century, I guess?

Nicky Yes. 1204 was the date when we pledged our allegiance to Britain.

Felice If people want to know more about World War Two and Jersey, is there somewhere they can look online?

Nicky Yes. Well, there’s a number of places. I mean, the Channel Island Occupation Society have got a website and they’ve got quite a lot of information. The Jersey War Tunnels, which is big displays about the war – that again, has a good, good website. There’s also a place called Jerripedia, which is a website for local history.

Felice And if other people want to go with a knowledgeable guide like you, how do they book?

Nicky Okay, well, I’m involved with Jersey Uncovered. We’re a group of six guides so you can find us easily on online JerseyUncovered.com There are other places, people who do bunker tours, so there’s a number of them. If you were just to search Occupation Jersey tours, you’ll find a number of things.

Roger Lewis, son of Dr. John Lewis, pictured in Longueville Manor. Photo: © F.Hardy

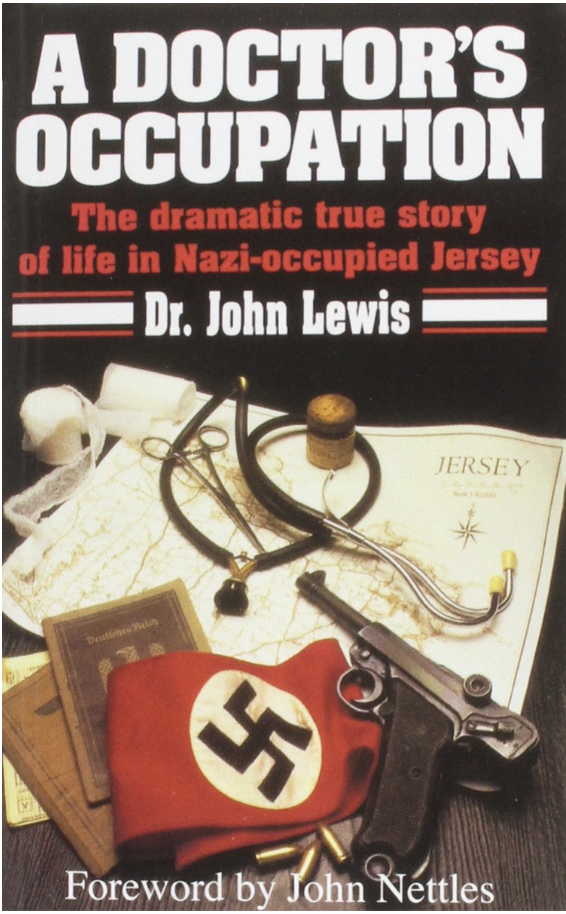

Peter To put some meat on the bones of the occupation. We met up with islander Roger Lewis, an old school friend of mine whose father was a doctor in Jersey throughout the war years. Now, as a teenager, I well remember Dr. John Lewis recounting fascinating tales of his practice during the occupation, moving around the island on an ancient bicycle to treat his patients. He had almost no drugs but great medical skills and a wicked sense of humour that kept him going through thick and thin. Now, sadly, John is no longer with us, but his book records his solitary existence throughout the occupation.

So, Roger, your father was a doctor in Jersey in the late 1930s, and then it looked like the Germans were going to invade. And your mother was heavily pregnant with your eldest brother?

Roger Correct, yes.

Peter The Germans were about to arrive, your mother was about to give birth and he thought he should probably leave and go back to Wales and look after your mother, quite rightly, while their first son was born.

Roger Correct. Actually what prompted it was at one time they decided to stay in the island and throw in their lot with the islanders. And then the rumours started coming through that the Germans were taking newborn babies back to Germany and my mother was going to be giving birth to a newborn baby over here, and that’s what prompted them to go back to the UK.

Peter And they got one of the last planes back?

Roger …and they got one of the last friends back, and then on to Cardiff.

Peter But then what happened?

Roger My father discovered that his partner had got cold feet and had left the island, so there was no one looking after the practice and he knew he had at least a dozen women who he’d promised to deliver their babies. So he thought he would have come back here and see if they could sort that out.

Peter While your brother hadn’t yet been born?

Roger He hadn’t yet been born. He came back on the boat. When we were being brought up, we’d always thought that my father got trapped here, came back, and the Germans walked in and that was it. It was only after my mother had died and he’d died that we had some lady who came out for dinner and she said, ‘Well, you know, your father actually opted to stay in Jersey,’ because the Bailiff called him in…with his great friend, a chap called Graham Bentley, and he had my father, ‘Look, please stay, you’ve got to stay. If Jersey’s to survive the occupation, we must have a young doctor here. Far too many old doctors here.’

And so she said, ‘Your father actually opted to stay,’ but we never knew that when we were being brought up. It’s very difficult to say to your wife, ‘I’ve decided not to come back to you after all, despite the fact you’re about to give birth.’ But it was a brave thing to do. So many people left Jersey and he actually came back.

Peter Then the Germans came in and all communication with Britain, with Wales, was cut.

Roger Absolutely.

Peter I think I’m saying it was a long time before he even knew that your brother had been born?

Roger It was nine months or something. He tried to get the BBC to play something, a certain song my parents used to dance to before the war, and if they played that, he would know that the baby was alright and being born. But the BBC said, ‘No, that could be a secret message for the Germans.’ How careful can you be?

Peter Clearly it was a very painful period of his life and some 40 years went by before he could bring himself to write it all down…in the 1980s.

Felice How did he remember everything? Did he keep a diary?

Roger He kept it in his medical daybook, apparently. He had a very good memory, actually. And he never let the truth get in the way of making up a good story either.

Peter He had a wonderful story about buying wine on the eve of the invasion. I think he went into his local wine merchant and did a bit of a deal, didn’t he?

Roger Yes. Nearly all the wine had gone, except for the best, you know, the Haut-Brion. And he said, ‘Well, I’ll take the lot. And they started,’ Well, that’s 21 shillings,’ and he said, ‘Well, the Germans will give you nothing except a kick up the backside for it. I’ll give you five bob a bottle.’ And that’s what he got it for. But that’s even quite expensive.

Peter And then he took up all the floorboards?

Roger He hid them under the floorboards.

Peter I remember him telling a story which is not in the book, actually, about making all this homemade hooch out of potatoes, I think ,when the wine finally ran out. And when they had a liberation party he had all these patients there, and he woke up in the morning and there were cars…

Roger People weren’t used to drinking.

Peter So he said to himself, ‘Oh, my goodness, I’ve kept them alive for five years and I’ve killed them.’

Felice What’s your favourite story about the war?

Roger I think it’s probably to do with the animals and the cow. You couldn’t have a single cow with under the German rules. My father had one and he lent it to a farmer so he could have a baby calf. And then so they had this baby calf at home…

Peter …and you had to hand over the calfs to the Germans?

Roger Yes. You had to, at a certain age. So my father went with a great friend of his. They went up and stole the calf, his own calf. They then distributed veal to all their friends. His farmhand rang him and said, ‘You won’t believe this doctor, but the calf’s been stolen.’ He said, ‘Don’t be stupid.’

Peter And on a more serious note, by the end of the war, the island was starving both the islanders and the Germans. Is that right?

Roger Totally. The only thing which saved them was the Red Cross parcels. I think that wasn’t until Christmas 1944. So much later. All the places like Colditz were getting Red Cross parcels much earlier. But I’m very grateful to what this Red Cross did. But otherwise they were starving badly. My father was very resourceful though, and my father would have been deported, but because he was in essential employment as head of the maternity hospital.

Peter He would have got a basic petrol ration, I suppose?

Roger He cycled virtually everywhere in the end.

Felice The book is called A Doctor’s Occupation by John Lewis, and it’s available from Amazon, Waterstones, and from Channel Island bookshops.

Peter Stay with us here in the Channel Islands for next week’s episode of Action Packed Travel. We’ll be taking a detailed look at Jersey‘s premier hotel, the magnificent Longueville Manor. It’s one of less than a handful of five stars in the British Isles, that’s still in private hands and family run.

Liberation Square in St Helier. Photo: © F.Hardy

That’s all for now. If you’ve enjoyed the show, please share this episode with at least one other person! Do also subscribe on Spotify, i-Tunes or any of the many podcast providers – where you can give us a rating. You can subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or any of the many podcast platforms. You can also find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. We’d love you to sign up for our regular emails to [email protected]. Until next week, stay safe.

© Action Packed Travel

- Join over a hundred thousand podcasters already using Buzzsprout to get their message out to the world.

- Following the link lets Buzzsprout know we sent you, gets you a $20 Amazon gift card if you sign up for a paid plan, and helps support our show.