J-P On a travel trip to Cape Town – abseiling off Table Mountain © John-Paul Flintoff

Peter Welcome to our travel podcast. We’re specialist travel writers and we’ve spent half a lifetime exploring every corner of the world.

Felice So we want to share with you some of our extraordinary experiences and the amazing people we’ve met along the way.

Peter This week, we’re talking to the remarkable John-Paul Flintoff – writer, artist, public speaker, master of the arts at large. John-Paul, that’s a pretty inadequate introduction, perhaps a better way of describing you is that your whole life appears to be a kind of happening. Can you explain what you do, because I don’t understand?

John-Paul Yes, I think you’re not the only one. Thank you for having me on. My name is John-Paul Flintoff. Most of my career, a number of years I would say, I’ve been a journalist, but I also do performance, I write books and I’m increasingly doing art – visualised art, something in the mix. I’ve been troubled by that too, by what do I do. I think the central thing is telling stories and self-expression.

Peter Which I suppose is what we do too really.

Felice What’s your background? Was writing – journalism – the first thing you did after you left school, or what was it?

John-Paul I should go back slightly because I always actually wanted to be an artist. And I had a very discouraging ‘O’ level interview with someone who said, ‘Oh, it’s very hard to be an artist.’ And I thought, as teenagers do…or maybe it was just me, I thought that meant you can’t be an artist. So I thought, I’ll go and do something easier, like be a writer. And so I did also love writing and my English teachers were very inspiring.

I did English at university and left university thinking, I’ll be a poet because all the people I studied were poets. And then I realised after about three days that you don’t make any money as a poet so I became a journalist – as if you make lots of money there…but you did make more then. I was very, very lucky that after a little while of being a specialist, I became a general magazine writer on the Financial Times so I could write about anything I liked.

Union Club portrait © John-Paul Flintoff

Peter Actually, it’s not a dissimilar story to you, Felice, in that you started off with art.

Felice I also went to art college and I was also discouraged, told, ‘Oh, you can never make a living from that.’ So I actually went along for an interview with Vogue magazine to work in their art department, and they offered me a job subbing instead. So I got into journalism that way.

John-Paul But how many art people do they think are good at subbing?

Felice Well, they said, ‘Oh, we see from your CV you’ve got English ‘A’ level.’ I talked to the sort of HR department, or whatever it is, first before seeing the person – and they said, ‘You know, we’ve got a job going there. Would you be interested? Nothing in the art department.’ So I said, yes ok.

John-Paul Did you realise at that time that you were sort of stepping onto a certain tramline and that you can’t kind of jump off and go into the art tramline race?

Felice No, I never did go back on the art one at all.

Peter Thirty years went by before you picked up a paintbrush again.

Felice That’s right.

Peter You’re doing it again now.

Felice Yes, I am. For myself, really. I’ve sold a couple of things, but not really seriously.

John-Paul I found it very hard to really, really – I did initially – to think I’m doing art other than just for myself. But eventually if I just kept on doing it, I thought, well, I’m the best person to be doing it for and if anyone else likes it, that’s a bonus.

Felice But we see that you’ve been doing online, you’re offering online portraits of people. Is that popular?

John-Paul Well, the funny thing is that just before lockdown I was asked to do portraits of the people in my local parish. So I drew 35 people in different places in the church. And then just as that was about to come out, lockdown arrived and a members’ club in Soho, the Union Club, asked if I would draw members of the club as a kind of ‘let’s keep everybody in each other’s mind’ and also fundraising. So they paid for me to draw their portrait live on Zoom and the money went to Soho homeless charity.

And it was such fun because I would have these people who I didn’t know just pop onto my screen, had to draw them there and then and talk to them. And one of them was late…sort of slightly missed the deadline. And it was a person called Olivia Colman. And I thought, OK.

She said, ‘Hi, it’s Olivia Colman. I’m sorry, I missed the deadline.’ And I though, that’s ok, it doesn’t matter about the deadline. But I had no idea whether it was like the Olivia Colman or not until the last minute and I didn’t want to let on my face, I didn’t want any sign of disappointment if it was another Olivia Colman. And so when the one who has actually won an Academy Award popped up on my zoom, it was massively intimidating but also gratifying and like everyone else, they were all great. But I had a nice conversation and drew her picture. So that was strange. But it was also a little bit like being a journalist and doing an interview. It was like this. It was like me seeing you and having a chat and sharing what’s going on.

Peter And also a little bit like sitting beneath the Eiffel Tower and drawing cartoon pictures of people who came by.

John-Paul Very, very much like that. You don’t exactly choose who you’re doing or what their setting is going to be. One thing I learned quite quickly was that if you draw people on Zoom, they’re likely to be fairly square on to you – you get head, shoulders and a fairly plain background. So I started asking people if they would sit well back from the computer and sort of turn sideways in their chair to try to channel my own inner National Portrait Gallery idea about what a good composition was. And they were much better. But it felt strange for everyone to be on Zoom but sitting way back over there.

Olivia Colman Union Club portrait © John-Paul Flintoff

Peter Well the portrayal of Olivia Colman is great. Did she like it?

John-Paul She seemed really, really delighted. Yes, I was very happy. What a nice person.

Felice And you’ve done other virtual things as well. You’ve been on a virtual pilgrimage?

John-Paul Oh, yes. This is something I hoped that we might talk about because this is, after all, travel. And this was another thing that I wanted to do in real life last year. Having studied English, I have always loved the idea of Geoffrey Chaucer and telling stories as you go somewhere. It’s important to do a pilgrimage because it gives you a reason to be walking and so you end up somewhere, so you’ve got a sense of direction. Within that sense of direction, you can pootle about and do all sorts of things.

And I love the fact that Chaucer has all these different storytellers slightly competing to tell the best story. So I thought I will do a pilgrimage from where I am in northwest London to Canterbury in April and somehow, I don’t know how it’s going to work, but I’ll get some storytellers to join me. They might join me on the odd day or something and I’ll record some stories.

And of course that didn’t happen. So then I went on to Google Maps, which on a big screen – I’ve got a relatively big Mac screen, on Google Maps you can do Street View. So I started walking down street view from home in the general direction of Canterbury, and I had people join me on Zoom.

So I was doing it. I mean, I was doing a virtual pilgrimage. The trouble is that there’s no discipline about being online, because you can go anywhere you like to. So I ended up going completely the wrong direction towards Cookham because I wanted to go and see where Stanley Spencer was…that’s north west. That’s not the direction of Canterbury. So I had to do a detour via Winchester. You’re in Winchester?

Felice Yes we are.

John-Paul So I spent about a year of my very, very early life in Winchester. So I thought, oh, I’ll go to Winchester and have a look round there. And then it all sort of rather petered out because I didn’t have the discipline to make a map or a plan. So this year I really mean to – lockdown or no, lockdown, I’m going to do a virtual pilgrimage in April.

Felice But you don’t get much exercise. It’s only for your fingers, not your legs.

John-Paul But you do get exercise if you do this thing that I’ve started doing, which is working for 25 minutes and then five minutes of press-ups or lunges or something, and then work for 25 minutes and then five minutes more press-ups or lunges or squats or whatever. So I’m actually getting quite a lot of exercise at the moment.

Peter So if 25 minutes came up, do you stop in the middle of an interview and then do your press-ups, or do you wait until the end of it?

John-Paul It’s only the work where I’m not actually live with someone like this, although it could be quite a good idea if I did that, I bet you’ve had no one on the podcast who stopped just to do some press-ups.

Peter And we’ve had some very strange polar explorers and who tell us terrible things about falling in the sea and what it’s like in the Arctic Ocean. But we’ve never had any virtual press-ups there.

John-Paul I’d be happy to do it, but you’d probably have to cover me audio wise so that the listener didn’t disappear.

Felice It sounds like something to try anyway.

Peter You’ve been described as ‘the most practical dreamer I know,’ and it was Harold Pinter who said, ‘Very good, very funny. In fact, it made me laugh.’ What made him laugh?

John-Paul In 2003, the day of the big march, the big protest against the invasion of Iraq, that day, I published a story in the FT about Harold Pinter. And they have a slot called Lunch with the FT. And so I met Pinter near the hospital where he was being treated for cancer, that I think probably was what he died of. And anyway, it had a sort of a joke at the end. Most people at the time hated Pinter’s politics, but loved his writing. And I said it’s just possible that for some people it’s the other way round. I think that was the thing that he laughed at most. But anyway, he left this message on my answerphone which I treasured, which is the Nobel Prize winning Harold Pinter who said that some of my writing made him laugh. After that, what do you need to do? Nothing. Thank goodness for that art teacher, hey?

Felice That’s probably the best you can ever get, isn’t it? Harold Pinter saying something like that?

John-Paul But I suppose the next step is to get multiple Nobel Prize winners.

Peter Have you got the actual audio telephone message?

John-Paul No, I really wish I had. I’d prized it for such a long time but then when you change your answer phone, that’s it. It was one of those old landline machines.

J-P and the python. © John-Paul Flintoff

Felice How annoying. But tell us about some of your actual travels – one that caught my eye was that you hunted and caught a python in the Everglades.

John-Paul Yes. Well, and I know you asked if I can send photos. I do have a picture of me with a python around my neck, a live one. But so I was thinking before coming on, here is the key, I’ve always felt slightly like a fraud with travel writing because although I’ve done lots of stories which were straightforwardly a story about travel – this is where you can go and you can do these things and I’ve always had this nagging fear that I wasn’t making it enough of a story. And I’ve got to come up with some amazing yarn or I’ve got to find the people who are doing something extraordinary and write about them rather than just say, here is a place and it’s really nice and interesting.

So I came up with this list that I sent you, and top of the list I suppose, is going hunting pythons in Florida because you just have to say those words and it’s quite exciting. And essentially, there was a hurricane that hit Florida in I think it was the 80s, but maybe in the 90s, and lots of pet pythons got loose. And now they were reckoned to be hundreds of thousands of pythons that can be up to 20 metres long, very long anyway, maybe even 20 metres, I mean, they can eat any humans. They can eat crocodiles. They do. They found one that had a crocodile inside it and not a small crocodile either.

Peter So it’s more of an alligator?

John-Paul Both, because there are crocodiles in the Everglades, too. There are any number of wild animals have been allowed. That’s where people go to take the animals that they can’t control, so they just dump them in the Everglades. So that python had been mating and having oodles of little pythons, which are sweet maybe at the beginning, but not so much later. And they’ve slithered all over the Everglades and they’ve eaten in some cases about 98 percent of the native furry and feathered Florida animals. So this is really, really a crisis.

The trouble is, there’s really no way of catching them, so the state has engaged a number of successful hunters who really know what they’re doing. But if you measure the Everglades, this enormous terrain over which you travel a certain number of levies, which are these raised roads, there might be several miles of marsh you’ll never get to go into because of all the alligators, and then you drive along the levee. So the only way the hunters really ever catch any pythons is if they happen to be crossing the levee at a moment.

So it’s really an utterly hopeless task, but it’s still quite exciting and I did follow an extremely brave chap into the marsh where he dived into the water. I mean, this is waters over a metre high, and he dived in and grabbed this python by the neck, just behind the head. That’s how you have to do it, otherwise you’re finished. And he wrestled with it. It was quite a big python. And I thought, this is very exciting stuff. So I wrote about that for a magazine. The Economist has a magazine called something like 1732, but it’s not 1732, it’s 1843 or something, it’s one of those years that was very important.

Felice Wow, that’s an amazing experience.

Peter So when you had it round your neck, was it easy to pry it off your neck?

John-Paul It wasn’t too hard. This one was probably about three metres long, so it was relatively small. And I was assured, because I was with two men who had guns, that it was going to be OK. And I’d seen one of them doing it, too. And he said basically, it’s only really wrapping itself around your neck because it needs not to fall off. So it’s not necessarily trying to get you. And I had it by the head, so I was holding its head. The rest was just…well, it was a python round my neck, as good and as bad as it sounds.

Felice We’ve had snakes to children’s birthday parties before now, when we used to live in London. You can actually get someone to bring a snake. I can’t remember what types they were.

John-Paul Was it because you didn’t like the children?

Felice It was little boys and they loved it.

Peter You lie them in a line and the snake slithered across their stomachs.

John-Paul Oh, wow. Great.

Peter And then we’ve done that in Australia, too, not actually touching the snakes, but some really nasty things, the sort of things that kill you in 45 seconds. I wouldn’t say we played with them, but we could see them very close up.

John-Paul Right. Are they brightly coloured?

Felice Very beautiful actually.

Peter You know, I always had a bit of a fear of snakes, a bigger one probably of spiders than snakes. But I do remember once in the south of Australia, near Melbourne somewhere, in a vineyard, there was a lot of straw on the ground and I saw something move in front of me. And then there was a track going up to where the car was and this enormous thing crossed in front of us. And the guide just held up his hand and said, ‘Just wait. He’s got just as much right to be as you have. But if he does come too close and if he does bite you, we’ve probably got about a minute or two to get something into you.’

John-Paul Some sort of adrenaline shot or something?

Peter I think it was a deadly poisonous snake, but he’d got the antidote. Ok, I remember many, many years ago I was hitchhiking through South America and I had with me a snakebite kit that my mother had bought me from a shop in London, a very famous shop called John Bell & Croydon in Wigmore Street. She’d bought it for me. And it was American, judging from the words on the instructions.

And it involved a razor blade and two suction cups. And basically, whatever you do, if you’re bitten, do not do the John Wayne thing and bite, get blood and suck it out because they will help move the poison around, so I’m told. But I did read the instructions and they said, ‘Having been bitten, kill the snake so you can show it to your physician.’ I thought…I was in the middle of the Amazon jungle, it’s not really likely that’s going to happen.

John-Paul You didn’t have Zoom with you at the time? You couldn’t sort of quickly phone in to your GP?

Peter I’m afraid it was a bit before that time, more like telex days.

John-Paul Send a Morse code message describing it.

Felice Just changing to another travel experience, you once saved your daughter from falling into a smoking volcano. That sounds dangerous, too.

John-Paul Oh, this was the thing I was talking about, where I was trying desperately to make a story. We just wanted to go on holiday in Italy but I thought, no, we’ve got to go and check out all the best volcanos. So we’ll do that. So we did Vesuvius, obviously, and we shouted and our tour guide taught us to sing some Italian songs so that would echo back up at us, and that was nice.

And then we went to Etna. And Etna wasn’t how I imagined a volcano with just one hole. It seemed to have holes all over the place and they’re all smoking and burning and gorging and gulping and making horrible noises. And my daughter at the time was very little and very easily grabbed by shiny stones. And there were lots of different types of colours on the stones at the time. And we had been told that probably if it wasn’t Italy they wouldn’t have allowed us up because it was so windy. But this being Italy – it was the Italians who said it – this being Italy, they didn’t really care, they said, ‘Just look out and be careful.’ It was really, really windy.

And she reached out to get…I think there were different metals in the stones, sort of iron, made it a bit red and something else made it blue and another one was yellow. She was collecting all these things and I said, ‘Can we maybe collect them at another time?’ And she was a very unreasonable little girl at that moment and she said that she really wanted them. And then she started to slip towards this hole that was smoking. And I grabbed her, I mean it was the wind as that pushed her, and I grabbed her by the hood to stop her fall. I ended up with a great story about volcanoes, but it was quite nerve-wracking, it was quite seriously angst-making and my wife was very cross.

Felice She wasn’t with you?

John-Paul She was, but she was cross about the whole general situation.

Peter We went up Etna, we walked up. An awful lot of ash and I felt very uncomfortable.

Felice We’ve skied on some volcanoes, too.

John-Paul In which countries?

John-Paul Wow, wow.

Felice And actually North America, too.

Peter It was not so much a volcano as a sort of vent. It was in a resort called Mammoth in California, where we were skiing down beside this vent. And I thought this is a really dramatic moment to propose, in deep powder snow. And I said, ‘Will you marry me? Skiing down towards her, lost my balance and fell over. So I had to wait miles until the reply.

John-Paul So you really did it while moving? Did you have to shout? What was it like from your end?

Felice Well, you just had to wait till he got up and went to the bottom of the run. And then I answered, I think.

John-Paul But you did hear?

Peter Yes, I did.

John-Paul Well, that really keeps you both on tenterhooks, doesn’t it?

Felice But we’ve also skied in Japan where the guide said, ‘Do not fall,’ because at the bottom of this there must have been a vent.

Peter No, that was a river at the bottom. We were in some sort of cherry orchard and there was bamboo and very strange trees to be skiing through. And this guy was actually a Kiwi, a New Zealander, and he was married to a Japanese girl and spoke fluent Japanese and was a wonderful combination of the two, actually, because he we could really understand what he wanted to do. And he was a great skier and we had a great time with him.

But we got to this very steep cherry orchard. And there was then it got a bit steeper beneath. And he said, ‘Ok, so we go down here and then we need to turn left where I turn left,’ and he said, ‘There is no margin for error because if you get if you fall to the right or go straight on, you’ll go into a river, which is always just under the boiling point, a thermal river, stream.’ And he said, ‘You’ll just cook like an egg, so don’t do it.’ We didn’t

John-Paul Had anyone ever had that happen?

Peter I didn’t want to ask really.

Felice He wasn’t going to tell us.

John-Paul But as I’m not a skier, how good did you have to be? I mean, you obviously are good, but did that worry you?

Peter I mean, you have to be a competent skier and it’s what we do for a living a lot of the time. So we were ok like that. But it focuses the mind when you’re told, actually always when you’re told, ‘Do not fall here,’ it’s the wrong thing to say, because that’s exactly the moment you would like to fall, probably.

John-Paul And it’s focusing on the thing that you don’t want the person to do. And that’s always bad advice because that’s what they’re thinking of.

Peter There’s a famous French extreme skier who came up with the phrase of saying, ‘Bon pour le concentration,’ which needs no translation at all. So it certainly is.

On another travel assigment. J-P at the bombed out Sarajevo Winter Olympics site. © John-Paul Flintoff

Felice So less exciting, I mean less dangerous, was flying into a storm system in Texas. Or maybe that was dangerous?

John-Paul That was very dangerous, actually, This was just amazing because they don’t get enough rain anymore, and it’s drying all the aquifers, agricultural land in Texas. And so I found out that there was this guy with this plane who flies into storm systems and his tiny little plane has flares on the wings, which he lets go and that causes the crystals – or whatever the chemical in the flares – causes the rain to to congeal into drops and then fall as great rainfall.

Peter That’s seeding, isn’t it?

John-Paul I think cloud seeding. And so I had this really strange experience of flying up in this tiny little plane in terribly shaky…it was really being whacked around by the storm system. So we’re flying into the storm system. And what actually happens is he goes into the storm system, which usually starts at about 5,000 feet, if memory serves, and then points towards the plane down directly at the earth and turns the engine off. And the storm system itself sucks the plane up to 25,000 feet and blows it out. And in that 20,000 feet of the flat seeding clouds, that’s where all that wonderful magic happens. But it’s terrifying, absolutely extraordinary business being shaken around in the thing.

Peter And I think you need to have a lot of belief in the pilot.

John-Paul And I didn’t really know that until I got there. I hadn’t thought through what was going to happen. And I’d been flown all the way to America and the magazine wanted the story and they had a camera crew. And I wanted to say, ‘Oh, actually, I don’t think I want to do this.’ All I could do is look at the guy and see that he had done it before and he survived.

Felice And often as journalists, you get put in these situations where you have to go ahead and do it because that’s why you’re there. But some of them can be a bit dodgy.

John-Paul Definitely.

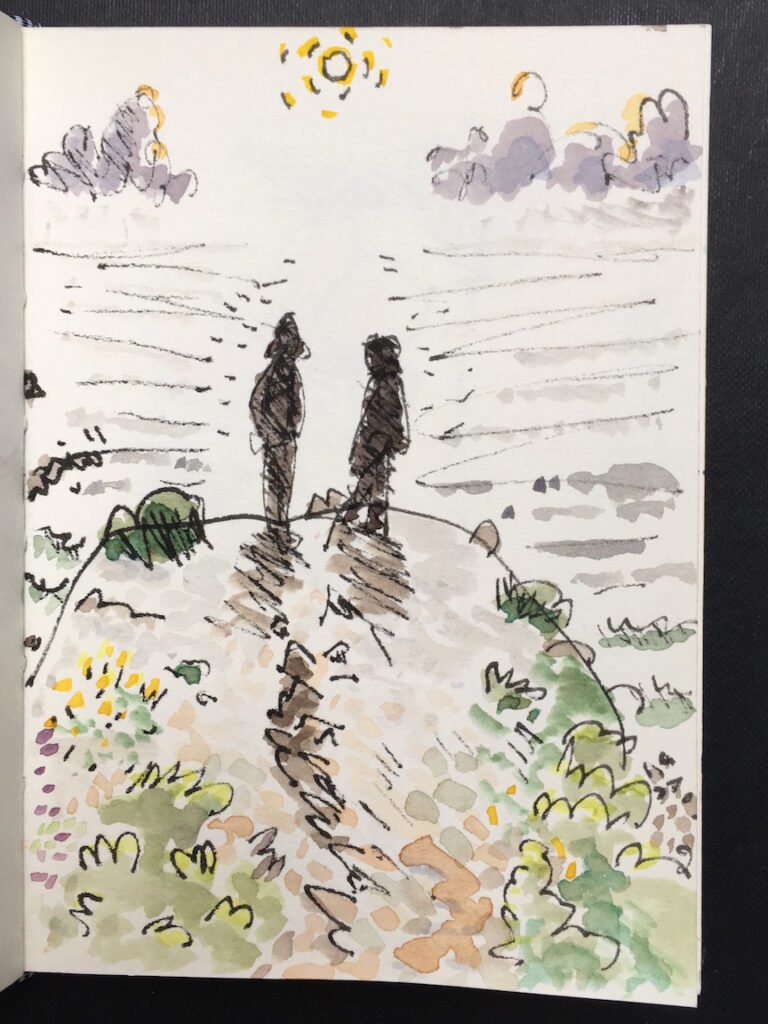

Travel sketch, Austria. © John-Paul Flintoff

Peter We are once asked to climb the Grossglockner, which is Austria’s highest mountain, in July, which we were assured would just be a stroll up through the Edelweiss singing songs from The Sound of Music, but of course it couldn’t have been a bigger lie.

We knew we were in trouble when we got to what was normally a mountain restaurant, a ski mountain restaurant in winter, we got there about midday and it was snowing by then. And then we had ice axes and crampons and things, and when we cross two glaciers and then we ended up on separate ropes going up to this refuge. If we’ve been on the same rope, we’ve been divorced by now, but fortunately on separate ropes it was ok. And when we got the top, we were helped on to the surface by a Sherpa, who was on a guest visit from Nepal. The biggest mistake I made in saying to myself, all these guys say it’s easy so it must be. No, it wasn’t.

John-Paul Wow. And I wonder whether you ever say, ‘That’s just not on. You shouldn’t have done that.’ Have you have done that?

Peter Oh, yes, definitely. But they just thought it was normal. And it was not a sort of huge feat of engineering, I have to say, because when we got to the refuge where we were to spend the night, Felice kept saying, ‘Oh, I can’t wait to have a hot bath.’ It wasn’t going to be that kind of refuge. I remember cleaning my teeth, standing out in the snow, putting my toothbrush rather pathetically into a bank of snow to get some water. But when we actually arrived and it was just about getting dark, our 22-year-old guide from the local village said to the boss, ‘Do you mind if I pop down and see my girlfriend now? I’ll be back up again by six o’clock tomorrow morning?’ And he just trotted off down the mountain again and came back up again, so for him it was just a stroll, but it wasn’t a stroll for us – we’re not climbers. Skiers we may be, but we’re not climbers.

John-Paul I suppose that’s the funny thing, isn’t it, is that travel writing is also about experiencing someone else’s normal and it’s not your normal. And I suppose the yearning is to be delighted by that. And sometimes the expectation is really, you know, not met.

Peter But I think it’s one of those things. Like if you’re a football writer, you don’t have to play football and you don’t ever have played football in your life. And you can do that quite happily. And if you’re a ski writer, you have to be able to do it and a few other things. But as a general travel writer, you don’t have to be able to do all these gung-ho things at all.

Felice But you’re expected to be expected to. So apart from writing, you also do quite a lot of public speaking?

John-Paul Yes. Thank you for mentioning that. I’ve got a book coming out on public speaking. It’s something I initially resisted writing. My agent suggested it and I thought that any book on public speaking has to be some sort of terrible liars, manipulative manual of how to make everyone do what you want and everything. I told him I didn’t like that idea. And I also thought who might who might write such a book?

And I think that my credential is that I think about it a lot, and I have done it quite a lot and have had a lot of failures as well as successes and I don’t mind talking about those. But I insisted that I should be allowed to call it A Modest Book About How To Make An Adequate Speech. And I thought that would put him off and I wouldn’t have to bother. But actually, the more I thought about it and the more he thought about, the more we both thought there’s definitely a space for things like this, because most books don’t that have that title

Peter And how do we get hold of this book?

John-Paul It’s published in February by Short Books, which is part of Hachette, and I believe it’s on Amazon now. And we’ve just finished designing the cover and it all feels a bit pointless at this time, with lockdown, at designing the back of the cover because all anyone on Amazon is ever going to see is the front. But we have You just have to take my word for it that it does have a back cover title.

Felice And did you draw the picture on the cover?

John-Paul Well, I did draw the cover and then they decided they wanted a different one, so their in-house designer, drew what I accept is a better cover, but I did draw the illustrations inside of a variety of different things. But some of them were famous speakers over time: Cicero, who, by the way, lots of people that really give a hoot about Cicero is one way or the other, except they might vaguely know that he was big rhetoric person and that he’s good at public speaking. But he actually had his head chopped off and pins stuck in his tongue by, as it happens, Mark Antony and Mark Antony’s wife because of something he said, so if you want to be better than Cicero, just make a speech and don’t have that happen. I think that’s encouraging for anyone.

Dnipro metro with cops. Photo: © John-Paul Flintoff

Peter To change the subject, you got arrested in Kiev, whatever for?

John-Paul Just for taking photographs in a tube station. I just really admired the blue tiles on on the wall in this tube station, it was a really strange experience, Kiev. This was quite a while ago. People didn’t ever give eye contact in public, nobody looked me in the eye and hardly in the hotel – it was bizarre. And just this extremely suspicious atmosphere.

And it was really a lovely place in many ways. It’s got lots of history and beautiful, beautiful tube stations. But I took this photograph and then these people who I didn’t understand, who had those very big Soviet style military hats…you know, the big round things, two of them took me into this room and shouted at me in Ukrainian. And I tried my hardest to express myself. They didn’t speak any English, so I switched to German.

And then interestingly their main focus, I came to understand, was why did I speak German? They really, really hated that. And so after probably just looking like an idiot and offering them my camera, this was before mobile phones so they couldn’t take the chip or anything. I said it, you know, I just want to go. But it was a funny because there’s a room in the tube station. But within the room there was a there was a metal mesh cage, and that’s what I sat in. So it wasn’t a terrible arrest because I was allowed to go after a while. But they shouted me a lot and I didn’t know what was going to happen.

Peter It’s quite frightening there, that sort of incident. It’s quite frightening because you don’t know what’s going happen next.

John-Paul No, exactly.

Peter It’s not because of what’s happening now; it’s what could happen next.

John-Paul Yes. I’ve been back to Kiev subsequently and it was much nicer.

Travel Sketch, Cornwall. © John-Paul Flintoff

Felice So where do you see yourself in the next few years? What do you think you’ll be doing in, say, five years from now?

John-Paul I really hope I’ll be doing a lot more art because that’s really exciting me. And one other thing that I think I’d like to do, I’ll just blurt it out because I haven’t told anyone about it but I’m really excited about it. It’s trying to get a whole lot of writers to work together over one 24-hour period to write a novel from scratch and get it printed by the next morning. I’ve got this kind of system in my mind which I’ve borrowed from computer programmers who have to very quickly put together programming so different programmers work on different bits.

And I think if I found the right writers who were willing to do it and editors and a layout person to crash-produce this thing and then it would be a model for schools to do the same thing. So that possibly in five years’ time, I might be something to do with an organisation that goes to schools and says it’s annual ‘write a novel day’. And then people in the school or maybe across different schools will capture that same thing.

So as you said Felice, earlier, with Vogue, you could have people who are just doing the art on the book and you could have someone doing subbing on the book and you have someone actually writing a framework for the plot – and someone saying, ‘I will do Act One Scene Three,’ and ‘I’ll do Act One Scene five,’ and then you have to have someone coordinating it, which is such a mind-boggling, pointless task. But I think people would learn a lot about collaboration, how the story develops, and about all of those other things like editing and design.

Felice Sounds like a good idea.

Peter A great idea.

John-Paul Thank you.

Peter You could get all sorts of interesting authors to involve themselves in that. What do you see the outline or the plot being? A detective story or a romantic novel?

John-Paul Well, this is exactly, you’ve put your finger on it, because I think if it were a repeated thing, you would have a guest who comes in, so maybe – fantasyland – J.K. Rowling would come in one year and say, ‘I’ll do the basic plot outline and it’s over to you.’ So maybe they would set a theme.

My original idea was that you could take a framework such as the loosest possible framework from, let’s say, a Shakespeare play. You’d say it going to be basically that story but we can change the century, we can change the gender, we can change all sorts of things, but we’ve got to follow more or less that story just to give people some kind of a rope to climb up that mountain.

Union Club portrait © John-Paul Flintoff

Felice If people want to find you, have you got a website?

John-Paul Yes, my website is Flintoff.org. So my surname is Flintoff, like the cricketer turned TV personality.

Peter Sorry, I should explain to our listeners in the United States and elsewhere who know as much about cricket as I do about baseball: Freddie Flintoff is a UK national hero with bat and ball. And are you related to Freddie Flintoff?

John-Paul Third cousin once removed, and the editor of the Sunday Times was very pleased about that. So in 2005, when we were about to win the Ashes, he phoned the editor of the section I worked on and said, ‘Get Flintoff to write about how he’s related to Freddie,’ and I had 24 hours to find out if I was. And I found the grave of a man who died in 1832, William Flintoff, who was our mutual ancestor. And then I went and had tea with his grandparents: my second cousins once removed, maybe third cousins, I can’t remember.

Peter And can you play cricket?

John-Paul Not really.

Peter John-Paul Flintoff, thank you very much for appearing on the show. And we wish you the very best of luck with your future travels and indeed your future book.

John-Paul Thank you so much for having me. It’s been a real pleasure and thanks for inspiring me to podcast.

Felice That’s all for now. If you’ve enjoyed the show, please share this episode with at least one other person! Do also subscribe on Spotify, i-Tunes or any of the many podcast providers – where you can give us a rating. You can subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or any of the many podcast platforms. You can also find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. We’d love you to sign up for our regular emails to [email protected].

You can also listen to John-Paul’s An Adequate Podcast

© ActionPacked Travel

- Join over a hundred thousand podcasters already using Buzzsprout to get their message out to the world.

- Following the link lets Buzzsprout know we sent you, gets you a $20 Amazon gift card if you sign up for a paid plan, and helps support our show.