The Great Bath

Peter Welcome to our travel podcast. We’re specialist travel writers and we’ve spent half a lifetime exploring every corner of the world.

Felice So we want to share with you some of our extraordinary experiences and the amazing people we’ve met along the way.

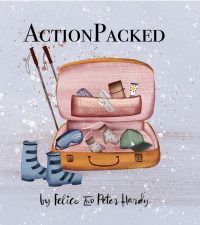

Peter So what did Jane Austen and the Roman emperor, Claudius, have in common? The answer, of course, is a love of bath water, or to be more precise, the mineral rich thermal waters, the mellow city of Bath in southwest England, or to give it its Roman name, Aquae Sulis.

In Jane’s day, Bath was the social capital of England, the party capital of Europe where the dancing in the Pump and Assembly Rooms went on by day and by night, with ambitious mothers earnestly trying to find wealthy husbands with their daughters in a marriage market decimated by the absence of suitable young men who were all off fighting in the Napoleonic wars.

Between bouts of matchmaking, mothers accompanied by elderly relatives, took the famous waters as a cure for cumulative ailments. Jane moved here in 1801, and this was the setting for two of her novels, Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. No, she didn’t find a husband, but she did enjoy the dancing.

Felice Some 1,760 years earlier, the community of Aquae Sulis here in the Quantock Hills, 115 miles west of London, had become the setting for the most important Roman bathhouse in Britain. It had a temple dedicated to the Celtic god, Sulis, and Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom. The Romans have long since departed from this corner of Somerset, but Jane Austen’s contribution can still be found in all her romantic novels. But the bath-temperature water still bubbles up through the limestone, and daily visitors from all over the world still drink this with tea in the neoclassical setting of the Pump Room.

Detail of the Roman Baths. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter For a private tour of the baths after dark, lit by flaming torches, we met up with local tour guide, Jess. Talking about water, a quick word here about WaterToGo. This is a British company that produces water filter bottles that magically make water safe and odour-free. Water to go simply filters out minerals, pollutants, chemicals and even viruses.

For the global traveller, WaterToGo is an essential piece of kit. Visitors to ActionPacked Travel can claim a 15% discount on these bottles. When you go to the checkout on either of these two websites, Watertogousa.com or Watertogo.eu. Just add a special code AP15 (Action Packed 15) into the box marked ‘coupon’ and away you go. But enough of that. Here’s Jess.

Jess So we’re standing in the Pump Room at the moment, 1790, where all of high society of Bath would gather for the season. They would meet people, they’d be wined and dined. And there’s a statue just behind you there. This is a statue of Beau Nash. So he was the main chief of the Pump Rooms and he would reign over everyone. So just before that, actually, he was in charge of everyone that was allowed in, and he was the Lord of Ceremonies. And they had a musician play; they still do it today at the piano.

Peter There was a sort of recess, a little dais. You actually have a chamber music or something.

Jess Yes, Exactly. We have a piano in the morning and we have a Pump Room Trio in the afternoon. That’s the cello, the violin and the piano. Yes, it’s really nice. It’s as it was back in those times.

Peter Nothing much has changed, you know.

Jess Exactly. So people still sit at the tables.

Felice And they can have the water as well?

Jess Exactly. So over here we’ve got the Pump Room’s fountain.

Peter A Roman type vase and the water being pumped up. And you could actually drink that, can you?

Jess Yes, I know it tastes a bit like…we’ve got a lot of iron in the water…it’s one of the main minerals, so it tastes quite metallic. And we’ve also got sodium chloride in there. So it’s quite salty.

Peter Salty and metallic. Doesn’t sound ideal.

Jess No, but it is warm. And supposedly it’s good for people. It’s been used as a ‘cure’ –. we say that in inverted commas – for many since the Roman period. Actually people have been coming to try the waters and to swim in the baths for about 2,000 years ongoing.

Peter So it cures all illnesses?

Jess Apparently so. So, yes, come come and have a try. But no, it’s not the best tasting water in the world, so we’ll see.

Peter And then this was, of course, the place where Jane Austen used to come.

Jess Exactly. So then we go early 1800s and this was still a very popular place to come…to come here and the Assembly Rooms, which are at the top of town.

The Pump Room exterior

Felice I did have some of the water once. When I was at school I came here, and I remember it wasn’t that nice. And the fact that it’s warm…

Jess It’s not very refreshing. It does shock people actually, that it’s hot. The water in this fountain is 45 degrees Celsius, so it’s a little bit cooler than a cup of tea and it gets pumped up directly from the source, which is underneath the fountain, and we’ll see that later on as well, when we go around. That’s the spring and environment times it was a sacred spring. But much later, now that we’re in the 1700s with the Pump Rooms, it was known as the King’s Baths. And there’s an inscription underneath the fountain there and it says King’s Spring.

Peter During the season, everyone will gather in this room or the Assembly Rooms as well. Is that right?

Jess Yes, exactly. It would be either here or the Assembly Rooms, they’re much one and the same. It looks quite similar to this. The Assembly Rooms are actually a little smaller than this building. The Pump Room is a bit larger. And they would turn up by carriage, day and night and they would come in and have a party and a dance, something to eat and drink.

Inside The Pump Room. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter And I read somewhere that one of the big problems were the lack of bathrooms.

Jess Yes, probably so. Actually, we still haven’t found the Roman bathrooms at all. We don’t know where the Roman toilets are.

Peter But I’m thinking more of the more of the Georgian bathrooms and much later.

Jess Yes, definitely.

Peter I also read that some of the hoop skirts women wore cups underneath their skirt.

Jess Yes. The sanitation back in the 18th century is not the same.

Peter It’s not very acceptable to us in this day and age.

Felice Is there a website where they where people can go?

Jess It’s all on Romanbath.co.uk – everything is on there. You can click on ‘Learning’ and there’s a lot of tabs to open as well. So if we go to the terrace that we’re coming up to now, we’ll be able to look over and see the Great Bath. in the 1920s, this was where people could have something to eat and drink as well. So it was a restaurant all along here. So if we look straight over and down, people get their first glimpse of the Great Bath.

Peter It looks like a large swimming-pool.

Photo: © F.Hardy

Jess Yes. By daylight it is bright green and this is due to the algae in the water. So the algae love the minerals, they love the sunlight that they get now that the pool’s open air. But in the Roman times, this would have been covered by a large roof and so it would have been a lot darker around the Great Bath. And this means that the algae couldn’t grow, so the water would have been clearer, really.

Peter But it’s really very impressive with these flaming sconces all along on the pillars, it looks really quite dramatic.

Felice When was the last time anyone swam in it?

Jess In 1978 was the last year that anyone got in the pools and swam around. In the 1960s and ‘70s, they had Roman Rendezvous, which were parties on the summer evenings, and people would pre- purchase tickets and they would come down. There would be a band on the side playing music; people be able to get in the pool and have a swim. People also swam in the Sacred Spring, which is our other pool. But because this is where all the water comes up and it’s 46 degrees Celsius approximately, it was too hot for people to withstand more than a couple of minutes.

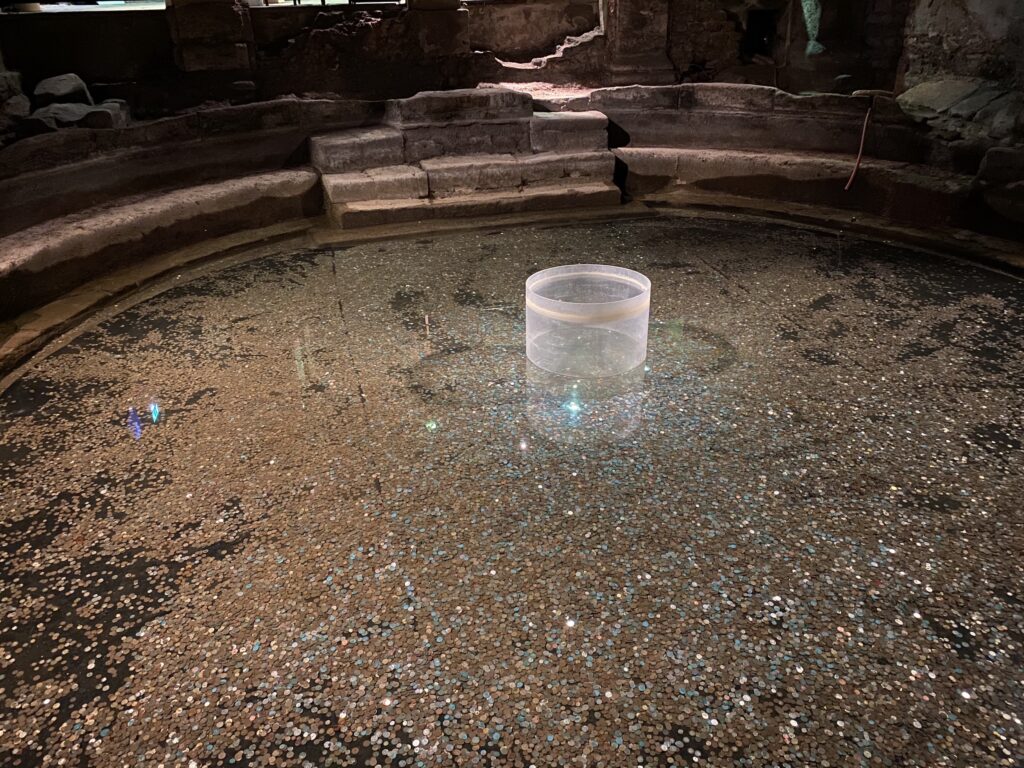

So this large Great Bath here, this is about body temperature, about 37 degrees Celsius all year round, more or less. And so this was the favoured pool for people to swim in, in the 20th century. The Romans never swam in the Sacred Spring – that was too sacred for them. They believe that’s where Sulis Minerva lived. So they wouldn’t go in that, it was just for worship. So I’ll take you go down this way next and we’ll go into the museum, which is one of the rooms.

Jess So the Romans, we think between some point in the first century. They arrived here in 43AD, so at some point after that. But it’s some time before 76AD because we have a stone with this date on it. So we know that the Baths were already established by 76AD. And it would have taken a bit of time for them to build, it was quite an architectural feat and they were doing it out of stone. So it would have taken a bit of time. But it was quite popular; you know the Romans had bathhouses in most of their cities, so it was a popular place to come.

And now we’re standing, looking at a model of what it would have looked like when it was first established, which is essentially a covering of the Great Bath with a wooden roof, and then the various pools and hot rooms around it. So it’s not that much larger than the Great Bath area. And then there was a temple just a few metres away from the bathhouse. So before the Romans arrived, there was a tribe living here called the Dobunni. And that’s where these coins are from.

So these pre-date the Roman period, but they were found on site as well. So presumably people that were living here before the Romans, they could come and enjoy the pools as well. They weren’t necessarily all cast out, and that’s where we have some of the coins really found in the spring, where people are making offerings. The Romans were here for about 350 years, so by the end of their time here, the baths had expanded.

Model of The Baths. Photo: © F.Hardy

Jess And we’ve got several temples now, many more baths and many more hot sauna rooms as well. So it’s quite a hive of activity. And then the temple now has been encompassed by a wall. And we’ve also got a tholos, which is a circular temple building just outside of the walls, and this is now where Bath Abbey sits. So with hundreds of people coming here every day to bathe and worship this is actually the only bathhouse in the entire Roman Empire that we know of, that’s attached to a temple.

Felice The Pump Room was built later? It happens to be next door.

Jess Exactly. The Pump Room actually was built right on top of where the temple sits. The first pump room dates from the early 1700s. But there was one before the one we went into earlier. And so the early 1700s Pump Room, while they were building it, they found the front of the temple. Some of the front stones of the temple were found underneath the pump rooms when they were laying the foundations, so people began to think then, in the early 1700s: ‘There’s something Roman going on down here.’

Felice Do we know if they had archaeologists at that time?

Jess They didn’t exactly have archaeologists. They have more sort of people that were interested and amateur archaeologists really, people that were into antiquities. And as that became more popular throughout the 1700s and 1800s, they found more of the Roman pieces in other buildings around Bath. So a lot of the medieval wall was built out of Roman pieces. And this wasn’t found until people stopped to have a look and said: ‘Well, hey maybe that’s actually part of the Roman bath?’

So over the years, that’s come back to us from around the site. There was the corner of an altar stone that was found propping up a church not far away.

Peter Where were people living? Was there an actual town here?

Jess Yes, there was. So from from the bathhouse and the temple complex, people would come here from far and wide. So people set up a business based on the tourism that Bath would receive.

Peter Which has gone on for the last 2,000 years. Exactly.

Jess Which is still the same today, really. That’s a small map of the town as it may have looked back in those times. It wasn’t as large as Bath is today, of course, but it was the main centre around the bathhouse and it fanned out from there. So other Roman villas have been found in the city. Lots of coins were found as well, actually about 13 years ago or so. And that’s the Beau Street Hoard. So they found all of these Roman coins, thousands of Roman coins underneath the floor of an old Roman house that somebody presumably buried and then left. And this is not far from here.

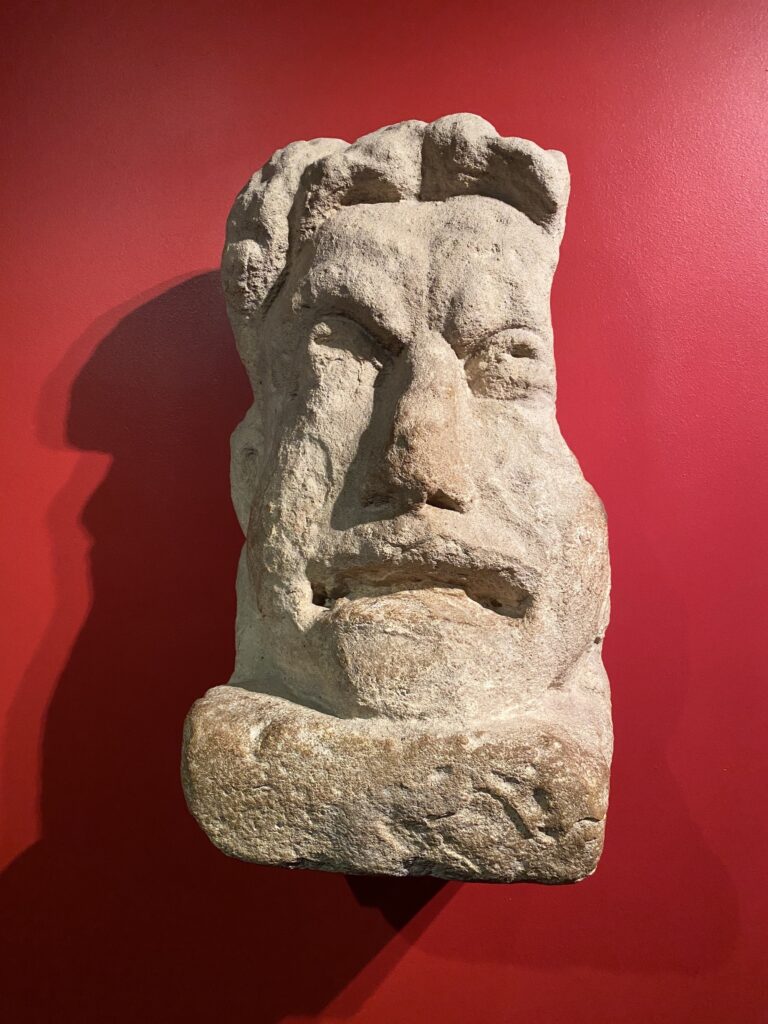

So round the corner here is the front of the temple, the main temple that I was talking about that was found underneath the Pump Rooms. And in the middle, we have this very striking face of what looks to be a man. So there’s several theories about who he could be. Some people think that he’s the god, Sul, and that’s Celtic. And the Romans, we think it was associated with their Minerva because it’s got a small owl in one of the corner pieces down there. Minerva was always associated with the owl for warfare and wisdom. We’ve also got a helmet as well, depicted on the front of the temple. So it’s like a puzzle piece, really, to put together. We’re not 100% sure who the face is – that’s still yet to be determined, but we call him the Gorgon.

Felice Are people still doing research into it?

Jess Yes. And the more we find out about the Roman baths, it may change what we know, it might change a bit of the model. They are excavating at the moment, actually, because the Roman Baths are building a new project for education and heritage, since we are a World Heritage site. So that is going to extend the museum a little bit more. People can see more of the collections that we’ve got, and a little bit larger within the site as well. All the front of the temples, all the buildings that we see around the site, all the stones, that’s all Bath stone. So it’s really a soft oolytic limestone.

Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter It’s all quarried locally?

Jess Yes.The Romans quarried on the south side of Bath and then brought it down from there. And much later, that’s where the architects of Bath – John Wood, Ralph Allen – also quarried the stone.

The special thing about Bath stone is the way that it can be cut. So it can be cleaved quite easily into rectangular blocks, which the Romans loved. But it’s quite stable, really. It won’t brush away, it’s not like a soft sandstone. It stood the test of time in that way, to be honest. This is part of a tombstone; we’re looking at the face of a man. He’s not looking very happy. So people came here for religious worship.

We’re going to go underneath the Pump rooms now, so it’s going to get a bit humid because of the hot water flows underneath here. Yeah. As they would have done 2,000 years ago you know. You can hear the water flowing through the site. We will come to the Roman drain later on. This is where all the water comes out of the Sacred Spring and heats our building and it goes to the Abbey and heats that building as well. And then it flows out to the River Avon.

So what we’re walking on now would have originally been open air. We’re about six meters below modern day street level: the Pump Restaurant that we started in. So back in the Roman times, people would make sacrifices on a large altar, a large table with several gods depicted around the sides. They have a different god and a goddess for everything, pretty much.

Peter But Minerva is the key goddess around here?

Jess Around here, yes. So the Romans took the Celtic god, Sul, and paired it with their own goddess, Minerva, and came up with Sulis Minerva. And that’s who’s referred to the most here in the Roman Baths on the inscriptions that we have. So you would have made a sacrifice on the altar and then come up the steps and gone to see the Sacred Spring, if you are allowed to. And, you know, most people were escorted by a priest or haruspex.

Felice So the heat from the Springs, does that heat the rest of the building?

Jess It heats a lot of the building, yes. So most of the museum, the downstairs level, keeps nice and toasty because we have the hot water flowing through. And then the Abbey started using the water as well for its new underfloor heating project. So that’s been a long time in the making, it took them a lot longer than they thought.

There were skeletons underneath the floor of the Abbey so that when they went down, the archaeologists had to look through all of these before putting down the pipes under the floor. But hopefully that will be completed soon. So as we go through the walkway here, we see the bronze head of Sulis Minerva.

Minerva’s head

So this was found when they were building a sewer in Bath in 1727 in the summer. The bronze, just the head now – she would have had a helmet on top and presumably as well, the body. But it’s been severed off at the neck. So we don’t know how it came to be destroyed exactly. But luckily, they were adding sanitation to the city in the 1700s, because that’s where she was found….by a builder. So she would have been in the temple, so not everybody coming to the Roman Baths will have been able to see her.

We’re now coming through the corridor where you get to see the Sacred Spring, as it was known 2,000 years ago. As I said, the Romans not swimming in this one, just offering things to the gods and goddesses. Sulis Minerva, really, who they believed was at the bottom.

Peter So we’ll just all here these artefacts?

Jess Because these were these were found in the spring. So these are curse tablets. And what people would do is if they had been wronged by somebody – a cloak stolen, for example, while at the bath house, they could write on a thin tablet of lead or pewter, metal and scribe a curse for that person, fold it up, throw it into the Sacred Spring and hope that Sulis Minerva would seek justice.

Peter That is absolutely fascinating. The theft of a pair of gloves, the document says ‘The thief should lose his mind and his eyes.’ Bit tough, isn’t it?

Jess But yes, it’s a bit much. But that’s what they did in those days.

Felice The theft of a blanket – the unusual spelling maybe is because the writer had dyslexia.

An artefact in the museum. Photo: © F.Hardy

Jess And then in here we’ve got more artefacts that were thrown into the Spring. So we’ve got some combs, some jewellery and some brooches, bowls, candleholder. So these are all things that people clearly valued. I mean, there’s a headdress here as well. It almost looks like it’s got the Golden sheen as well, part of a headdress…so that went into the Spring too. So quite a lot of things really that were all preserved underneath the floor of the Sacred Spring.

So what happened after the Romans left, the townspeople almost wanted to forget about the Roman takeover… they built on top of the remains. And so the site was lost for over a thousand years and then rediscovered in the late 1800s. But the townspeople after the Roman period did continue to use the water, but they weren’t using any of the Roman buildings, but they were using the Roman stones. As we mentioned earlier, they were recycled in churches and medieval walls. So underneath the floor that was added across the Sacred Spring, when they took that out in the 1980s, they found all of these remains.

We can see the steam coming off of the water because it’s so hot. So the water’s heated; it fell as rain about 10,000 years ago and then it slowly percolates down to about 4,000 meters into the earth’s crust where it’s naturally hot, and it picks up this heat, gets to about boiling point and then it travels along from the Mendips. It is then the water travels down from the Mendips and it hits a hard bedrock called Alias Clay and it can’t travel any further at that depth.

So then it starts to come up and there’s a fault underneath Bath, a fault line called the Pennyquick Fault. The water comes up through there into three places in the city, and this is the largest one of them. This is just over a one point one million litres every day. So it’s a quarter of a million gallons coming into this pool. And the other two are underneath the Thermae Spa, which just a few meters west of where we are now. The pool at the moment, that water is about two meters deep and it’s at Roman level.

And then after the Romans left, they added that floor over the top. We can see the remains of the floor around the edge, like a shelf now, and that’s where it stayed. So the water was actually a bit higher.

The Roman drain. Photo: © F.Hardy

The Great Bath was the level at which the whole Roman city was. So it’s going to get a bit loud here, because all the water that comes out of the spring is going through a Roman drain, a Roman overflow drain.

Peter Okay, it’s pretty loud.

Jess And that’s down here. All right. Yes. So you can hear all the water, all those millions of litres.

Peter Oh, wow. Look at that.

Jess So I don’t know how good the sound is here. So what we’re looking at is all the water coming out of the spring. Some of the water from the spring has gone into the Great Bath, so it’s not quite all of the water that’s come up from the source. But this is a Roman-built drain and any extra water they didn’t need would come through this way. So we can see the Roman archway as well, the infamous architecture of the Romans there.

And then where the water comes over the limestone rock, it’s bright orange – this is the iron in the water. So the iron salts have turned the rock on the left an orange and left an iron residue on top, so it’s quite bright. And then it flows down underneath the museum where we take some of the heat for our building. And then it goes down to the River Avon, which is about 350 meters away from where we’re standing now.

Peter And it comes out quite warm when it goes into the river.

Jess Yes, it is. I couldn’t say exactly how warm, I would be guessing mid-20, 20 or 25 degrees Celsius by that point – because it’s travelled a fair away. And some of it is siphoned off to be used for the Abbey heating project as well. And it comes out just below Pulteney Weir, if you’ve ever seen that one, just below the waterline, you can see the water’s a little warmer than the river. They’ve got all the steam from the water there, because, again, it’s about 46 degrees Celsius.

And then we’re walking now really in the footsteps of the drain. And they’ve got a clear floor over here to see that the water carries on its journey down through the Roman drain. And here it is coming out over here. And it’s really gone that way for 2,000 years. So most of the drain that the Romans built is quite large. And that’s because if they needed to get down and repair it, somebody could. But they built it very well. They built to last, the Romans.

Peter Two thousand years later and it looks as good as new.

Jess Then we’ve also got various gemstones that were found in this area. So from people’s rings, these little gems would fall out and a lot of them ended up in the drain that comes out from the Great Bath. And then all the water from the Great Bath joins that overflow drain and, again, it goes down to the river. We’ve got all different colours, beautiful, tiny, tiny pitchers as well. We’re going to head out to the Great Bath now.

Peter So after Jane Austen, which was when she came to live here, I believe, after that period during the 19th century, it was very popular in Victorian times?

Jess Bath fell a little bit into decline after Jane Austen. Yes, it’s not so much a place that people would visit. They still had the hot water and the baths, but the town actually became very dark because the industrial revolution turned the bath stone a black colour from all the soot, so it was quite a dark place really throughout the 19th century.

Peter It was not a good place to be.

Jess Yes. And I think that’s one of the reasons why they wanted to see the Roman side of bath and open it up again and see what was going on.

Great Bath at night. Photo: © F.Hardy

Felice Can members of the public come and see it at night?

Jess Yes, they can. So at the moment, night for us is about four o’clock. These are called the flares and these are not Roman, unfortunately, as you’d probably guess. So these are turned on about 3pm, 3.30pm when it starts to get dark, and then we’re open until five o’clock in the week and six o’clock on the weekends at the moment.

Felice So winter’s actually a good time to come here?

Jess Yes definitely. And we’re a lot quieter as well. In the summer, we run late summer evenings until 10pm normally. And at this time the flares are on during the evening as well. And that’s normally July and August. So I’ll show you the East Falls which are just over here. So in the in the first century AD, the bathing was mixed. So when the baths were first built, men and women could all bathe together. But in the second century, Emperor Hadrian, he forbade joint bathing, so they had to split everybody up. And this meant that the women would be on one side of the bath; they would actually be here in the east baths in the east of the city, and the men would be over in the west baths.

And then we also have hot sauna rooms here. So a regime that would they would have to go to when they came to the baths. So the first order of service really was the apodyterium, the changing room. They would leave all the items of clothing in there. And as we saw, sometimes things got stolen. And then they would go into the tepidarium, which was a lukewarm room to acclimatise to the temperature. They would have a massage in there with hot scented oils, and then they would come into the caldarium. And that’s where we are now. The caldarium was the hottest room at the bath house, the hottest sauna, and the Romans heated the floor with an underfloor heating system.

Underfloor heating. Photo: © F.Hardy

Felice So did the Romans invent underfloor heating?

Jess I would say yes, they did. I think yes, definitely, 2,000 years before we had underfloor heating. And then once you have gone through the cleaning regime with the three rooms, had the oil removed from the body, then you could go out and swim in the pools. So a little bit like before you get into the public swimming-pool today, you’ve got to shower before you go. Yes, the Romans were doing that as well. So they were they were really big on cleaning.

The Great Bath is about five foot deep, about a metre and a half. So it’s actually not as deep as some people think, and that’s the question that we get asked the most: how deep is it?

Peter No diving?

Jess No. And then at the bottom, we have the original Roman lead lining that they put down to waterproof the bath. We drain the bath to clean it about four times a year and check the condition of the stone steps leading down it on all sides, check the condition of that lead, and also just to flow through some of the algae…the algae build-up that we get these days as well. Of course, they wouldn’t have had in the Roman times. So out here would be a hive of activity in the Roman times. And then here in front of us is the inlet channel where the water comes from, the Sacred Spring – or the King’s Bath – into the Great Bath.

The Sacred Spring, full of (modern day) coins. Photo: © F.Hardy

Felice It says, ‘Do not touch the water.’ Is that because it’s very hot?

Jess It’s again, because it’s not treated, so with the water, you know, the risk is just bacteria – anything that might survive in the human body, really. But we encourage people to hold their hand above the water because you can feel the temperature even then. And this water is sitting at about 45 degree Celsius. Yes. So not boiling. Hotter than a bath, but it’s also a bath.

I shall go up now. This is the last part and this is where you get one last glimpse at the sacred spring through Roman archways. So the Roman arches now act like little windows you can peer through and have a look at the spring. A bit closer than what we previously have, so you can see the rings I mentioned earlier.

Peter Yes, indeed.

Jess They were donated, mostly in the early 1700s, by people that were cured by the waters – by grateful bathers. They are made out of bronze. And they usually have an inscription on them to thank the waters. And then people could hold onto them, if they were submerging themselves and they were having difficulty swimming, then you could just hang onto a ring there. There were also archways, little alcoves around the baths as well. So you could sit in those until the water healed you. But because it’s so hot, a couple of minutes in here, you’re going to feel pretty faint.

Peter Do you know what’s the temperature of that?

Jess About 46 degrees. There’s a long history of people coming to worship this spring and, after the Romans left, using the water to swim in. And so this is why Bath it’s called Bath, not because of the Great Bath.

Peter Jess, thanks very much indeed for appearing on the show. And we hope that the guests will return in 2021 and Bath will continue its 2,000-year history.

Felice That’s all for now. If you’ve enjoyed the show, please share this episode with at least one other person! Do also subscribe on Spotify, i-Tunes or any of the many podcast providers – where you can give us a rating. You can subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or any of the many podcast platforms. You can also find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. We’d love you to sign up for our regular emails to [email protected].

© ActionPacked Travel

- Join over a hundred thousand podcasters already using Buzzsprout to get their message out to the world.

- Following the link lets Buzzsprout know we sent you, gets you a $20 Amazon gift card if you sign up for a paid plan, and helps support our show.