Sam in training in Scandinavia. Photo: © Chris Shirley/Haus of Hiatu

Peter Welcome to our travel podcast. We’re specialist travel writers, and we’ve spent half a lifetime exploring every corner of the world.

Felice So we want to share with you some of our extraordinary experiences and the amazing people we’ve met along the way.

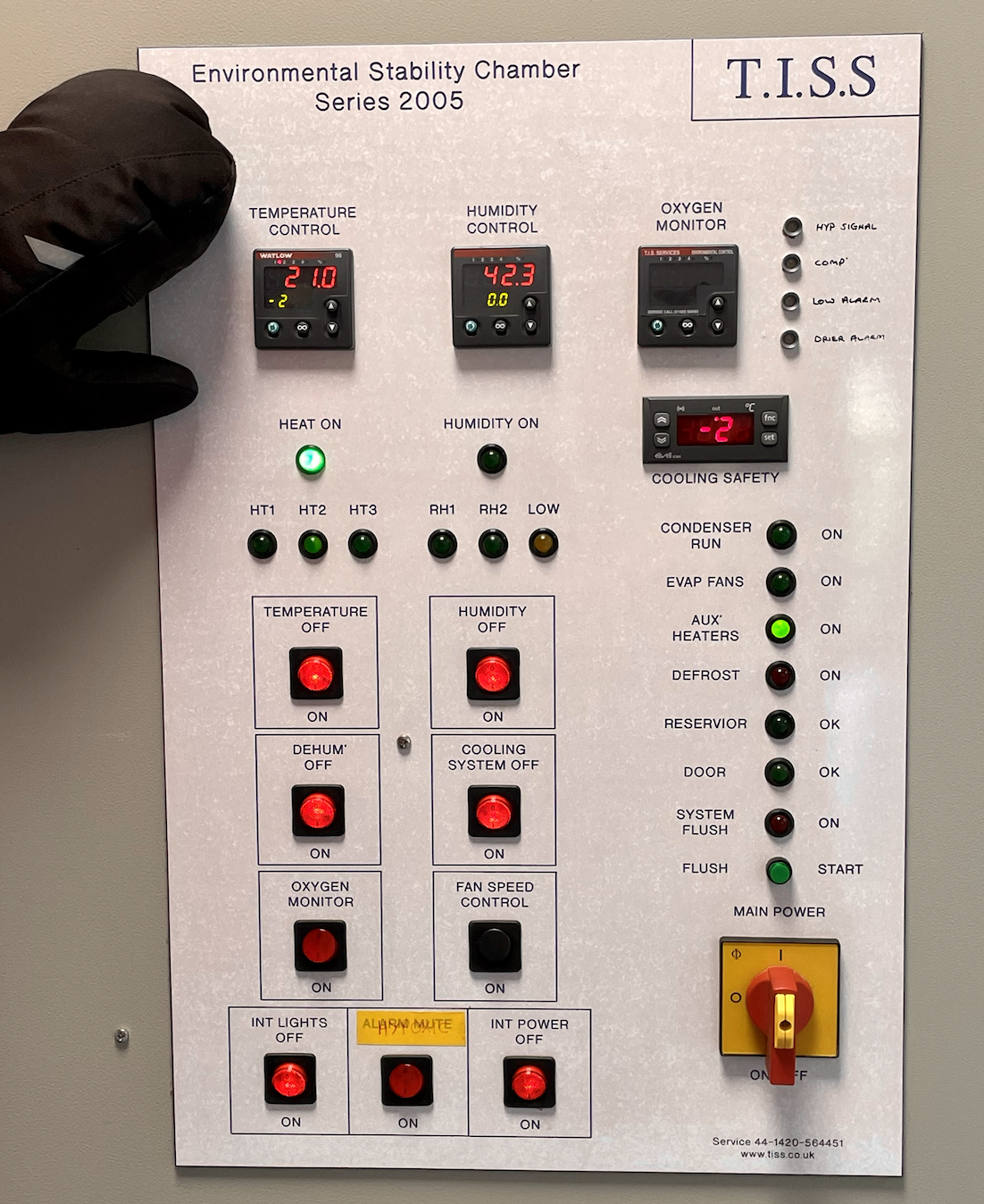

Peter This week we’re down in Devon at Plymouth Marjon University, where I’ve somewhat reluctantly agreed to undergo a series of tests to discover whether or not someone of advancing years like myself is both physically and mentally fit enough to ski to the South Pole and beyond.

Now, the daily summer temperature down there at the bottom of the Earth during our winter up here north, hovers in the high -20°Celsius. Well, I can tell you right now that after a long, shivering session in the uni’s environmental stability chamber….well, what I’d call an industrial freezer…that thankfully, age has a few advantages. I’m nowhere near in good enough shape to follow in the footsteps of Scott and Amundsen. Anyway, for me, it would be a thoroughly unpleasant way to spend Christmas.

However, I was sharing the fridge with former Royal Marine, Sam Cox, who’s embarking on a gruelling record attempt to ski nearly 2000km alone across Antarctica for at least 75 days. He plans to plod across the ice while pulling a sled, weighing an incredible 160 kilos.

The idea was to do a series of physical and mental tests to see how we both performed, firstly in the warmth of the university gym and then later in extreme cold conditions.

Sam on the treadmill. Photo: © F.Hardy

The first test involved riding a treadmill while wired up to heart and breathing monitors. To simulate the effort required to pull the sled across the ice, we wore a seven-kilo harness each, with the mill set to a steep incline. For the second test, we had to unpack and assemble the ten components of a Primus stove and then repack them. Sounds simple? You try with frozen fingers. Before we got going, I asked Sam what made him undertake this extraordinary project in the first place.

Sam So this was born of lockdown boredom. I’d been away with the military, I’d just left the military, and I’d been away for a couple of months when Covid was just bubbling in the background. Then we got pulled off this big exercise and I’ve been really busy. So I went from being really busy straight into UK lockdown to then needing something after I’d finished watching telly, every programme under the sun.

So it came from that and then went back to work for a few more months and the second lockdown came, I decided that this project was going to become an actual thing, rather than just a background activity that I was looking into. So once I told a few people I’d committed then and started properly doing the planning. So by the time I’ve finished, it’ll be coming up four years from there, and then I’d just get sponsorship. Unfortunately, however, I think it’s sort of a blessing in disguise, actually. I worked on a lot of a few other things instead of rushing through. Actually, I’m probably better now than I would have been. I’d have gone last year. I am definitely more prepared.

Peter Anything you’re nervous about it?

Sam Not really. I don’t think it’s really in my nature to be nervous. I don’t really sweat over small stuff or worry about things overly. I just try and get on with it and I’m comfortable in my own capabilities and comfortable in what I can achieve. The only thing I’m nervous about, I’d say, would probably be the conditions – that’s the one thing I can’t control, and it’s one thing that can hugely impact the speed I go out, which will hugely impact the outcome of the expedition.

Peter kitted up for the first test. Photo: © F.Hardy

Sam For example, in the year just gone there were really bad conditions and the guys were really struggling to make 15, 20km a day. I need to make on average about 25 or 26, give or take, to be done in the 75 days I want to do it in. Whereas in previous years, a couple of years ago, they ended up people were doing 30km a day quite happily without any real issue. And that’s purely down to conditions.

Peter Presumably in the late afternoon you’re going to think, ‘Should I push on for another couple of clicks or should I stop?’

Sam It’s that famous thing, isn’t it? Whereas if Scott had continued for another, I think it’s 11 steps….he is quoted as another 11 steps every day…he would have made it back without running out of food. So it’s one of those that…I’ve got timings in my head, but if I’m doing really well and I’m moving really well, I’ll quite happily push for another hour because, you know, extra 4 or 5k here and there will save an extra day off the end. And same with the other way round: if I’m not feeling great, do I continue pushing because every time I stop early, it means I’ve then got to go even further the following day? Overall I want to do it in 75; ideally, I’d want to do it under 75.

Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter So, Sam, we’re standing in the cold chamber and it’s just a mere -18° degrees at the moment. That sounds like a warm day in the Antarctic.

Sam Yes, It’ll be around about this most days, I think, give or take. It gets colder as you get closer to the pole because you go up in elevation, so it moves more towards -30.

Peter And -30 is the highest, lowest temperature you’ll reach?

Sam Yes. So that’s sort of the summer temperature in Antarctica, obviously it’s the southern hemisphere. So that’ll be the colder side of it, and then you have windchill on top which can really whip up temperatures.

Peter I sort of visualise Antarctica being flat ice, but it’s by no means always flat is it?

Sam: No. In terms of the grand scheme of things, it’s relatively flat. But then what happens is it doesn’t snow down there. It’s actually a desert, Antarctica, so you get a lot of ice crystals and dunes that build up through the wind. So it’s really fine sandy snow ice crystals that build up into ridges that can be about two meters tall in some places, so you end up trying to get over those with 160 kilos being dragged behind you.

Peter Can you do it? How do you shift? You’ve obviously practiced, but moving like moving over a five-bar gate or something.

Sam You can go round them. Again, they’re not like dead upright, they’re sort of mini sand dunes is probably the best term, or moguls in terms of alpine skiing. So you either go around them or find a small bit, or they have little collapsed bits. So they’re navigable, but they do slow movement relatively badly.

Peter Knowing nothing about Antarctic exploring, there’s no risk of going through the ice? It’s a solid ice cap you’re on?

Sam Yes. So there’s a few sections on…there’s a couple of crevasses – one I have to go up and one I have to come back down. So there’s a few crevasse fields that I’ll be navigating around. But the ice cap at the South Pole is about 2800m thick. Yes, it’s solid. And if I’m going through that then I’m not coming back out so but that that doesn’t happen.

Peter If you meet a polar bear something’s gone very wrong indeed hasn’t it?

Sam I hope not. I have met a couple of friendly penguins; if there’s a polar bear down there either I’m lost or he’s lost.

Peter But there are no mammals, am I right in thinking there are no mammals?

Sam I think penguins, seals and whales are the only native animals and birds to Antarctica. They’re all around the coast. Then in the central parts there’s not even bacteria that grows. So like I said, it is a desert, so it’s completely devoid of life…bar the research stations that are dotted around.

Peter Obviously you’re carrying all this stuff and not leaving any litter. You’re still going to have the same weight at the end when you’ve brought everything with you?

Sam I’ve got about 1.4 kilos per day worth of food. I can leave human waste behind.

Peter That’s ok is it?

Sam Is it organic waste. Then the final degrees, the final 110km is a scientific area, you bag everything up and bring it and then take it to the end. So there’s 220km where I’ll have to bag everything. But then apart from that…

Peter Then in the middle you can leave your poo behind?

Sam I have to take it with me. But before I get to the final degree, the last degree, I can leave it in situ. It’s a big place, so hopefully no one stands in it. So every evening I have to check in anyway for safety and then the guys on the other end of the radio will give me a weather report, if there’s a big storm coming in, they can let me know. And then I suppose the mental aspects are the one thing you can’t really train for.

Peter Do you have music with you?

Sam I will do but I don’t want to rely on it, though. For me, I want to use it as a bit of a motivator rather than the norm. I know a few people have lost headphones or broken headphones, and then the one thing that they like to do breaks completely, and then they don’t have that. It’s all daylight, there’s no night time. Like I said, I’ll do 12 hours and try and keep relatively regimented with keeping a 24-hour day.

Peter What about keeping warm, that’s going to be hard isn’t it, keeping warm all the time?

Sam So I’m stood still in the -18° cold chamber and my fingers are starting to get a bit tingly. I’m sure yours are now without a glove on.

Peter But I’ve got a glove on.

Sam There you go. Even worse, but once you’re moving, it’s relatively easy to keep warm. And then I’ve got some more mid layers I can add, and then I’ve got a couple of big jackets for when I stop. Then once you’re in the tent because there’s 24-hour daylight, the tent actually warms up quite nicely. So relatively warm to +5, +10 to 10.

Peter Quite warm.

Sam So it means you can be in a jumper rather than in thick, thick wool and stuff, which is quite handy to dry things out.

Peter Will you get wet, presumably from moisture in the area?

Sam It’s really dry, so I shouldn’t be getting wet. The only way I’ll get wet is either I spill something on me or I’m sweating and I’m going to try and stay away from sweating – that then freezes to you and that’s how you end up with frostnip or frostbite of certain areas. And the idea is to work a level where you’re working hard but not so hard you’re sweating.

Peter What about if the worst comes to worst and you have a problem, a serious problem? Is it possible to evacuate from the middle of nowhere?

Sam So the support team, the ones I speak to every day, they have the ability to get out to you. But that’s weather dependent and location dependent. If I’m in quite a tricky area to get to, it’ll take them several days to get to me, if it’s bad weather, they have to wait till the weather clears off. It’s relatively easy for them to get to me, but again it’s situation- and condition-dependent.

Peter So how close is the nearest human being going to be to you?

Sam Oh, it’s tough to say. Well there’s a research station at the Pole. So probably the furthest I’ll be from anyone will be about 700km, which is the longest leg from where I start to, to the Pole. So 700, 800km-ish.

Peter But there are very few places on Earth where you can actually be that alone.

Sam I think the famous thing that ocean rower say is the closest people to them are the guys in the space station flying around. So I’m not that far away from people, but it’s still a long way.

Peter assembling the Primus cooker. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter Oh, no, it’s time for the Primus stove test. They’re ready to go. Is that the tricky bit? Thank you guys, it’s really good. Are you feeling cold now? You’re looking like you’re shivering a bit now.

Lab assistant Yes, just a little bit cold.

Peter Have you ever been this cold before?

Lab assistant No, I can’t say I have.

Peter It’s crunch time: How did I do overall?

Dr Joe Laydon Well, not the best, I’m afraid. You know, I think one of the one of the tellers really was from the outset was the task on the treadmill. You know, as soon as we popped that additional weight on, physically that was quite challenging. So I think in comparison with Sam, where he more or less had not much of a change in energy expenditure, because he’s quite used to that sort of load carriage.

Peter You’re saying very politely that I may be just a little bit past it?

Joe No, I don’t think we can say you’re past it, but I think you’re not there at the moment. So maybe a bit of work to be done and you can get back to there.

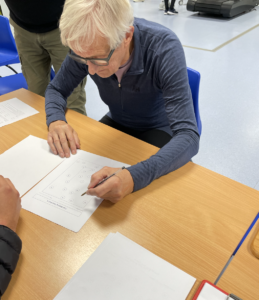

Peter completing the letters and numbers test. Photo: © F.Hardy

Peter You think so?

Felice He hasn’t got long, though, to do that in.

Joe Well, that’s fine. Then obviously when we’re in the chamber, we could feel the cold and that task in itself – just trying to put the transit together – in the lab and the normal environment, where you’re comfortable, you’re fine. You can focus solely on just putting that transit together. But when you’re sat in front of the fan in a -20° environment, where you’re cold and you think, ‘I need to do this quickly,’ that’s when your mind starts to wander off to other things: about the discomfort, about the loneliness or whatever. Then the ability to do that simple task just goes out the window, which you saw yourself as well.

Peter So what’s the ideal sort of weight and age for someone to do something like walk across the Antarctic?

Joe Oh, a good question. I think it’s a difficult one to answer that really, because we know that, you know, young people have got high levels of aerobic fitness but they don’t necessarily have the stamina and the mental resilience to undertake a task like this. As people develop that mental resilience, they start to lose the physical fitness. So it’s a fine balance, I would say.

Peter Somewhere in your 30s might be the more ideal time.

Joe I think probably, somebody like Sam who is in a good physical prime but has a lot of experience with his military background and has been in that environment before. He knows how to deal with the challenges. So I wouldn’t say that there’s a necessary age, but I think it’s about the elements of preparation that are key.

Felice How much training does Sam do?

Joe Oh, that’s a good question. I think he probably trains most days a week, but my understanding is the work that he’s been doing has been working at a lower intensity and looking at that duration.

Peter Presumably there’s a question of stability, that you’re reaching the same level, you’re burning up the same number of calories going at the same speed. Your heart’s remaining much the same.

Joe So as the fitness improves and fitness develops, one of the things that changes is your ability. You increase your ability to burn fats. You become more efficient at transporting oxygen around the body. You can essentially conserve that carbohydrate availability. That’s one of the things that we were testing on the on the treadmill. We find that when Sam got on to the treadmill, we put that additional load on, his increase in carbohydrate utilisation didn’t change by much. I think it was maybe a 10% increase.

Peter In my case, a lot.

Joe I think you were up to about 40% of increase. So a considerable shift towards carbohydrates. And if you think about somebody doing a marathon, they talk about ‘hitting the wall’ and that hitting the wall is really when they get to that carbohydrate depletion. You know, we’ve normally got that sort of intensity, about 90 minutes’ worth of carbohydrate availability. Unfortunately because of the intensity, you stepped into that, you’d be hitting the wall quite quickly.

Peter In the first ten minutes.

Felice So if someone wants to come and do this and come and train and see what the conditions are like, can they do that? Can someone just book?

Joe Yes, we’ve got a great facility here. It’s open to the public. We’ve got sports science support services, we’ve got clinics next door where we can look at prehabilitation rehab. You know, we can do the fitness testing. We can look at aerobic capacity, body composition, undertake health checks.

Peter As a doctor, how did you get into this?

Joe Well, I initially I started off…I had a background in outdoor pursuits. I used to be outside in the cold and in the heat, and really that was what drove my interest in it – in terms of what makes people get involved with this and how do we cope with it? Just purely from a fascination, in terms of how I could deal with it myself. Then as I was working in the outdoors, I saw a lot of people struggling with the heat and struggling with the cold – when I was mountaineering. So that’s where it came from. Then I got interested in the physiology and I found that even more fascinating, just in terms of how our body works and how we can respond and adapt to these different changes.

Peter It’s come a long way in the Antarctic since Scott and Shackleton.

Joe Well, I think physiologically we probably haven’t changed that much, but technologically we’ve got much more sophisticated equipment and clothing and textiles and the ability to carry loads. The food: I think Sam has got a great example of he’s got a really well considered nutrition ration packs. We’re looking at having the right percentage of carbohydrates and fats. We’ve got questions about digestibility. You know, food tolerance is a key as well because trying to consume, you know, 7,500, 8,000 calories a day is quite a challenge. I think Mike Stroud, when he when he went across the Arctic, they carried a lot of fat. Mike Stroud and Ranulph Fiennes actually they struggled – the palatability was an issue. So now we’ve got to the position where we’ve got ration packs that have got palatable food, but the right combination of fat, carbs and proteins.

Peter They taste quite good.

Joe They do. Well, I think you’ve got one.

Peter So we’re going to let you know tonight, this evening. That’s dinner this evening when we get home.

Felice What sort of food would Scott have taken, I wonder?

Joe Oh good question. I’m not sure, really, but I think they were there quite some time, and I think they were probably trying to consume the food that was maybe available.

Peter They end up eating their ponies, I think probably?

Joe Yes. I think back then there was a lot of concern about proteins and high protein diets, and I think if you look at the Inuit tribes they tend to have a high protein diet because you don’t get many vegetables and corn growing in the Arctic. I think that’s probably more of an acclimation issue than an adaptation issue.

Peter What about the dangers of injury? Obviously, if you’re pulling a sled like that, anything can happen. I mean it’s very heavy. You’ve got to be very careful because there’s no one coming to help you, is there?

Joe No, there’s not. I think that’s the thing. With somebody like Sam, we know that load carriage does increase the risk of injury. But with preparation, proper preparation. What Sam will have gone through is he will, you know, been skiing. He will start then skiing with a small load, with a lightweight pulk, and then increasing the overall weight of it. You know, injury is always a possibility. But I don’t think you can focus on getting injured, you’ve just got to focus on staying strong, staying fit and hoping it doesn’t happen.

Peter Thank you very much indeed.

Sam Cox

Joe No worries.

Felice If people want to find out more and book, what’s the website?

Joe Just Google ‘Marjon’ – it will take them to there. They can see a list of all of our courses and opportunities that they can get involved with.

Felice So, Peter, what did you think of it? Were you freezing cold in there?

Peter Well, actually, it wasn’t too bad. I mean, they jacked the temperature up, or rather down, to about -30 with wind chill, maybe a little bit more. But I had got some pretty efficient clothing on, so it wasn’t too bad.

Felice You say wind chill, there can’t have been any wind in there?

Peter Oh yes, there, because they put two big fans in there just to make it more uncomfortable. And they didn’t want me to wear my big parka because they wanted me to get cold, so that my cognitive abilities would slow down. I have to say, my cognitive abilities are pretty slow anyway, so they were an awful lot slower by the time I got a bit of cold.

Felice I think he said you used 40% more carbohydrates than someone young. Is that right?

Peter I’m sure that’s right. Certainly it’s not a game for an elderly statesman like myself.

Felice Unless you want to lose a lot of weight, perhaps, but then you wouldn’t be fit enough.

Peter I think there are easier ways of losing weight than walking across Antarctica. But it was surprising that once I got inside and tried putting together the Primus stove, it was really difficult because it’s pretty complicated and difficult to do, fiddly to do, at room temperature, but once you drop the temperature down by 30°, it slows you down and your temperament changes. You get more annoyed more quickly with just a fiddly bit. So if you are Sam, he takes it all very quietly and very calmly, because he’s been training to do this for months and months.

Felice I suppose it’s the same as in the heat. Everything’s much more of an effort.

Peter Yes, but I think the cold actually slows your brain down as far as I was concerned.

Felice Now, if you want to try this, you really need to be someone who lives in the southwest, ideally near Plymouth. Or you could get on the train. Or perhaps you fancy a day out or a weekend in Devon and you could go and do this.

Peter Yes, why not. They have all sorts of courses and you can go in the cold chamber. It’s not a very big room, but it’s a bit like being in a meat larder. But it’s cold in there. So what shall we do about dinner tonight?

Photo: © F.Hardy

Felice Well, we’ve been given a lovely box of expedition rations. So we might start with the chicken in black bean sauce, and that’s dried so you have to add water and heat it up. And then we might have some high protein nut butter that’s chocolate and orange flavoured…and 568 calories.

Peter You have that as a sort of drink, do you?

Felice I think you can have it as a drink, or you can have it as a snack or a pudding. Then there’s some energy bars they gave us and a shot of coffee, a single shot of coffee that’s 60 calories – that seems quite high for coffee. And then for breakfast tomorrow, some high protein porridge mixed berry flavour: 454 calories.

Peter You can follow Sam’s progress on his website www.Frozendagger.co.uk – we wish him well.

Felice Thank you very much for coming on our show. It’s been fascinating. That’s all for now. If you’ve enjoyed the show, please share this episode with at least one other person! Do also subscribe on Spotify, i-Tunes or any of the many podcast providers – where you can give us a rating. You can subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts or any of the many podcast platforms. You can also find us on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. We’d love you to sign up for our regular emails to [email protected]. By the way, we’re no 7 in the Top 20 Midlife Travel Podcasts.

You can listen to our other podcasts about Polar explorers here – Tom Avery: North Pole, South Pole and Verbier, Exploring the Planet with George Bullard.

© Action Packed Travel

- Join over a hundred thousand podcasters already using Buzzsprout to get their message out to the world.

- Following the link lets Buzzsprout know we sent you, gets you a $20 Amazon gift card if you sign up for a paid plan, and helps support our show.